6.Yamazaki Masakazu’s Ideal of the Advanced Consumer Society

If Maruyama Masao was the leading leftist intellectual when it came to politics and free speech in the postwar era, then perhaps his counterpart on the right was Yamazaki Masakazu.

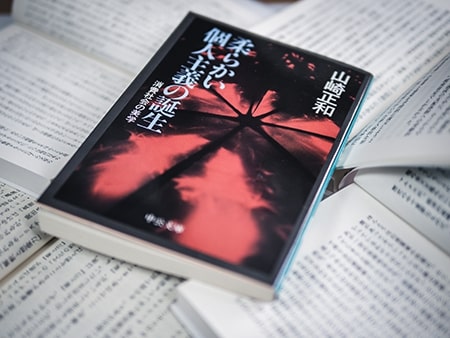

Yamazaki was born in Kyoto in 1934. He graduated from the philosophy department at Kyoto University’s Faculty of Letters. He began writing stage plays while attending graduate school, and won the prestigious Kishida Prize for Drama for his 1963 play Zeami—based on the life of Noh’s greatest dramatist. He later became a critic and won the Minister of Education Award for Fine Arts Best New Talent Award in 1972 for his book Geki-teki naru Nihonjin (The Dramatic Japanese). In 1973, he won the Yomiuri Literary Prize for his book Ogai: Tatakau Kacho (Ogai: Combative Patriarch). He has also translated classics like Tsurezuregusa (Essays in Idleness) and Hojoki (An Account of My Hut) into modern Japanese. He won the Yoshino Sakuzo Prize for his 1984 book, Yawarakai Kojinshugi no Tanjo—Shouhi Shakai no Bigaku (The Birth of a Soft Individualism: The Aesthetics of a Consumer Society).

Between the 70s and 80s, Japanese society underwent a period of rapid economic growth, and was in the midst of shifting from an industrial society to an advanced consumer society. In Yawarakai Kojinshugi no Tanjo, Yamazaki made bold, astute predictions about how people’s lives would change, and how consumption would evolve.

The influx of Western influences after the Meiji Restoration sparked Japan’s industrial revolution. Workers became increasingly specialized, working ever more diligently for the sake of efficiency, and it became a virtue to accumulate wealth rather than spend it on extravagances. That kind of asceticism, as well as people’s unwavering belief in the security of company hierarchies, and the tendency to relegate oneself to within the boundaries of your area of expertise—Yamazaki characterized all of these things as elements of a “rigid and hard” notion of individualism. In such an industrialized society, consumption is merely a means to feed the labor force so that they can work longer and harder.

Around the 80s, Yamazaki says, the desire to express oneself began to truly take root in the Japanese consumers’ psyche. In terms of fashion, they started buying more and more brand-name products, opting for design over functionality. Wardrobe and makeup became tools to make oneself look cooler or cuter. Yamazaki also argues that it was around this time that the Japanese began to “consume time”—that is, they were increasingly caring about spending their time in a manner that meant something to them. This is what he means by a shift from an efficiency-based industrial society to a consumption-based society. And this is what people mean these days when they say young people have stopped buying cars and other material things, and instead spend their money on “experiences”. He calls this desire to express oneself and consume “soft individualism”.

The important point here is that for Yamazaki, self-expression and the consumption of time are ultimately social activities. Self-expression is not for self-satisfaction but is rather a way to communicate and connect with those around you; the act of another person fulfilling their desires is also a fulfillment of our own. In terms of time well spent, it’s not about quickly opting for a set meal and stuffing it into your mouth as quickly as possible; instead it’s about eating with friends, spending time mulling over the menu, and savoring the food put out in front of you—quality over quantity. Yamazaki says the ultimate form of this type of social activity is the tea ceremony, where people “spend an inordinate amount of time and extend every courtesy just to consume a pinch of green tea powder.” In other words, he turns to tradition and ritual for his conception of the ideal of the consumer society. The conclusion reflects his lifelong fascination as a playwright with Japanese traditions and Japanese life.

7.The Japan That Can Say No: Why Japan Will Be First Among Equals

The 1989 book of essays, The Japan that Can Say No: Why Japan Will Be First Among Equals, was co-authored by Akutagawa Prize-winning author, conservative politician, and later Tokyo governor Ishihara Shintaro and Sony co-founder Morita Akio. The book became a massive bestseller in Japan, and many unauthorized translations were made and circulated in the U.S. and around the world.

This book was published amid a time of trade friction between Japan and the U.S., when Japan was riding high on the bubble economy and exerting more and more influence globally. Ishihara and Morita’s basic vision is that Japan should stop being a mere “yes man" to the U.S. and other countries around the world in business and in international relations.

At the time, Ishihara was a leading Liberal Democratic Party politician, serving as the Minister of Transport under Prime Minister Takeshita Noboru. Writing from the perspective of a politician, he argues that Japan should be respected as a world power, and that Japan should assert itself more when dealing with the U.S. He criticizes the state of the Western and Anglo-Saxon dominated world order and says that Japan should use its technological superiority in industries such as semiconductor production as a negotiating weapon. He also voices his opinion that Japan should end the U.S.-Japan security pact and defend itself.

Morita, who had lived for a period in New York and had extensive familiarity with Japanese and American business practices, criticizes American businesses and puts forth what Japan has to do to raise its international standing. He says that American businesses focus too much on mergers and acquisitions and short-term profits, to the detriment of its product development, manufacturing power, and overall long-term livelihood. He also suggests that American executives receive too much income. (Many Japanese readers may think of former Nissan CEO and now fugitive Carlos Ghosn.) He also asserts that the Japanese need to do more to study Western culture and languages, and that if it truly intends to become a world leader, it must help build up Asia and give more foreign aid.

Critics of this book accused its arguments of being too emotionally based, and that Ishihara’s assessment of Japan’s technological superiority was completely unscientific. Others point out that the book’s focus is on politicians and executives, and as such it ignores the average consumer and average worker. That being said, it’s important to consider Ishihara and Morita’s intention: not to speak ill of the U.S. or Japan, but to send a wake-up call to Japanese policymakers and executives. And the authors don’t just put forth a vision, but also concrete strategies to place Japan in a position to say “no".

8.Umehara Takeshi’s Reinterpretation of Ancient Japanese Culture

In my previous article on the intellectual giants of prewar Japan, I covered the Kyoto School of philosophy, which was led by figures like Nishida Kitaro and Watsuji Tetsuro. Umehara Takeshi’s work—and especially Umehara Japanology, his theory of Japanese culture based on Buddhism and Shinto—are an extension of the ideas of the Kyoto School and are an integral part of postwar Japanese nihonron and nihonjinron.

Umehara Takeshi was born in the city of Sendai in Miyagi Prefecture in 1925, and grew up in Aichi Prefecture. He spent his high school years during World War II, and the experience would greatly shape his interest in philosophy. In the final years of the war, a severe labor shortage would lead to middle schoolers and high schoolers being mobilized to assist the munitions industry; when a factory that Umehara was working at was bombed by the U.S., many of the student workers were killed, although Umehara was able to survive by reaching an air raid shelter. He began to feel that he would almost certainly die during the war, and began reading every book on philosophy and religion he could get his hands on to learn more about death. His studies would spark his interest in Nishida Kitaro and the other Kyoto School philosophers, and he would enroll at Kyoto University. While he would almost immediately be drafted into the army, the war would be over within a couple of months, and he would resume his studies.

Umehara studied Western philosophy extensively before shifting his focus to the study of the Japanese psyche, which he explored through the lens of Japanese Buddhism. His study produced the seminal book Saicho to Kuukai—Nihonjin no Kokoro no Furusato (Saicho and Kukai: The Home of the Japanese Spirit). The book compares and contrasts the philosophies of Saicho and Kukai, two of the leading figures of Buddhism in the Heian Period, and explores how Japan developed its own distinct variety of Buddhism. Saicho taught that people could attain Buddhahood through practicing virtuous and good deeds, while Kukai taught that people could attain Buddhahood without discarding their present mortal form. Umehara attempted to rediscover the spiritual home of the Japanese through their teachings.

Umehara’s interests extended beyond Buddhism, and he was also deeply interested in ancient Japanese history. He argued that the Kojiki—an early Japanese chronicle of myths, legends, and oral traditions—was not historical fact but not entirely fiction, either, and was instead an ideological book intended to form the basis for a Japanese nation under the ritsuryo codes—a historical law system of the Nara and Heian periods based on the philosophies of Confucianism and Chinese Legalism.

In his 1972 book Kakusareta Jujiga: Horyuji-ron (The Hidden Cross: A Theory of Horyuji), he put forth his alternate theory that Horyuji, a Buddhist temple in Nara, was built to appease the spirit of Prince Shotoku. Umehara’s bold, original theories would collectively come to be known as Umehara Japanology.

Umehara Japanology was in many ways defined by its rejection of established academic theory, and was also a skeptical worldview fostered by Umehara’s wartime experience. He believed that nationalism was the true culprit that had brought Japan to the brink of destruction, and put his theories forth with the goal of emancipating studies of ancient Japan from the kokugaku (an academic movement emphasizing Japanese classical studies) label. He was an ardent defender of the Peace Constitution and Article 9, and remained a steadfast leftist intellectual throughout his life.

That being said, what’s intriguing is that even as a liberal intellectual, Umehara was quick to draw a line between him and the shinpo-teki bunkajin. Whereas they rejected Japanese culture and history, Umehara attempted to reinterpret it through his own unique perspective. For example, he was an adamant believer that “polytheistic religions are inherently more tolerant than and superior to monotheistic religions". That is both a product of his deep study of Japanese Buddhism, as well as a reflection of the liberal philosophy of embracing diversity.

9.Ideologically Opposed but Intellectually Similar: Nishibe Susumu and Sataka Makoto

As we’ve seen up until this point, the clash between liberal “progressive men of letters" and conservative thinkers has been the fundamental framework for almost all intellectual debate in postwar Japan. The figures I’ve written about in this article have all made high-level, well-thought out arguments, but attempting to approach and understand them individually is a futile exercise. This is perhaps why so many have discounted them as too difficult. But if you approach their works in terms of how they relate or respond or otherwise engage in discussion with other contemporary works, their message suddenly becomes clear.

In the foreword to Nihon no Shiso (An Explication of Japanese Thought), Maruyama Masao explains what he considers a fundamental problem: “Even when you look at the more logically thought-out and understood philosophies of scholars and thinkers, the discussions are limited to within the same school, or within the same religion. There are very few debates held with an intellectual equal from another field, and those debates hardly ever pave the way for something new." With that in mind, I’d like to finish this article by looking at conservative intellectual Nishibe Susumu and liberal intellectual Sataka Makoto.

Nishibe Susumu was born in Hokkaido in 1939. He graduated from the Faculty of Economics at the University of Tokyo, and later became an assistant professor, and then a professor at the school. However, when he recommended the anthropologist Nakazawa Shinichi for a teaching position (I wrote about Nakazawa and his research on Minakata Kumagusu in my article on prewar Japanese intellectuals) only to have it be rejected by the faculty, he resigned from his position in protest. Later, he began making regular appearances on the debate show Asa made Nama-Terebi, and became famous as a conservative intellectual. He took his own life on January 21, 2018.

Sataka Makoto was born in Yamagata Prefecture in 1945. He graduated from the School of Law at Keio University. He worked as a high school teacher and then as the editor-in-chief of a magazine on economics, and then became active as a liberal intellectual.

Nishibe and Sataka co-starred in the talk program Nishibe Susumu/Sataka Makoto no Gakumon no Susume (Nishibe Susumu and Sataka Makoto’s Encouragement for Learning). On each episode they would cover a variety of topics, and the wide-ranging discussion would bring out their thoughts on public figures, books, magazines, music, and more. The tone of the show was hopeful, and meant to encourage young viewers.

Nishibe and Sataka have released a number of their discussions as books. In Besutosera Enjo (Bestsellers Go up in Flames), they skewer works by Katsuma Kazuyo, Murakami Haruki, Uchida Tatsuru, Takenaka Heizo, Shiono Nanami, and Inamori Kazuo. The key takeaway here is that their intention is not to badmouth the authors, but rather to criticize the greed of publishing companies and editors, whom in their view have increasingly been publishing books “of no substance". They also voice their misgivings about TV pundits who spout off with only a rudimentary understanding of those who came before them, and are thus unable to foster constructive discussion.

In the December 2015 issue of Weekly Diamond, Sataka published an article entitled “Nishibe Susumu is My Intellectual Opponent but We Both Despise the Same People”. In it, he talks about the biggest surprise upon starting his show with Nishibe was that they both were interested in the same thinkers and hated the same kind of people. “We both share contempt for those without any weight behind their comments, who are all talk and no action,” he says. In times when ideological divides seem insurmountable, we could stand to learn from how these two engaged in civilized debate, with a larger goal of elevating the discussion.

10.Epilogue

Japanese people have a tendency to avoid difficult tasks and put off everything that feels troublesome.

When the so-called intellectuals of the left rejected the prewar Japanese polity and suddenly began championing democracy in the postwar era, they did so because it was easier to start anew than it would have been to truly reckon with Japan’s past. The lack of an ideological touchstone explains why the Japanese have been able to accept of new modes of thought so flexibly; perhaps it is also the reason why they have been unable to learn from history.

The same thing can be said about media pundits publishing new shinsho paperbacks and making the rounds on TV. They write and speak in simplified terms and questionable analogies, which sound appealing but do not withstand even the most basic scrutiny. Certainly, part of it is that both the pundits and publishers are only responding to the needs of the market, but they are equally guilty of fostering those same trends. Their goal is not to stimulate discussion but to sell books, and every wild claim and spineless statement is a calculated move to that end.

In recent weeks, the new coronovirus outbreak has got the Japanese—and the entire world, it seems—in a panic. Every day on TV you see Japan’s opposition parties criticizing the government without offering any constructive ideas of their own; meanwhile, business owners’ main concern is for financial assistance from the government; then there are the citizens, who are preoccupied buying all the masks and toilet paper they can get their hands on. Given Japan’s reputation for coming together in times of crisis, you would expect the same to happening now. But instead, everybody seems to be looking out only for themselves, while simultaneously criticizing the government for not doing more for them. In the foreword to Kyodo Gensou-ron, Yoshimoto Takaaki writes about how the Japanese consider the state as akin to a “bag" that enveloped its citizens completely. The Japanese ultimately believe that in the end, their government will save them. This type of dependency is exactly what Doi Takeo meant when he was writing about amae.

Each party leader talks about how they want to engage in a thorough discussion of the issues, but what they really mean is that they want a safe space to bombard the LDP with criticism. When their trolling does not provoke a satisfactory response, they boycott. Not once do they offer concrete suggestions or alternate ways forward. Not once do they attempt to deepen the conversation. Not once do they demonstrate a desire to solve the issues at hand. Meanwhile, important political decisions are delayed time and time again. That’s the kind of attitude you’d expect from people who dismiss challenging philosophical texts for their difficulty, who mistake the freedom democracy affords them as an excuse to make demands without ever taking responsibility. In the end, they rest easy in the knowledge that their government will save them. But with freedom comes responsibility, and that responsibility can be troublesome—but it is crucial that that responsibility is taken seriously. The books I’ve covered in this article all understand that point.

At the beginning of this article, I wrote about how Maruyama Masao argued that Japanese thought lacks an ideological touchstone. Well, the Japanese scholar of Buddhism Sueki Fumihiko just released a new Iwanami shinsho paperback called Nihon Shisoushi (The History of Japanese Thought). In it, he attempts to shed a light on the evolution of Japanese thought throughout the ages, and he identifies two through lines: the role of kings, and Shinto and Buddhism. The book is only available in Japanese, but check it out if you get the chance.