1.Prologue

This first installment in our series on the history of world cinema is divided into two parts. In part one, I start with the invention of the movies and cover the developments that led to Hollywood becoming the epicenter of the American film industry. In part two, I cover 12 classic films from the silent era between 1900 and the early 1930s. The films, some of which are now more than a century old, not only paved the way for movies to become the dominant form of mass entertainment for much of the 20th century—they continue to exert an undeniable influence on Hollywood today.

2.The Invention of Movies

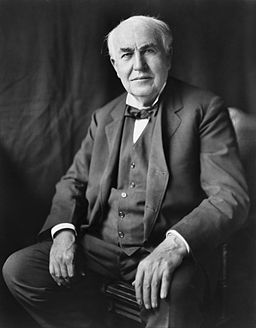

In the late 19th century, inventors around the world had begun trying to develop motion-picture machines to record and reproduce moving images. In terms of setting the stage for cinema to become a commercial enterprise, the devices invented by Thomas Edison and the Lumière brothers were particularly significant. Edison had already invented the phonograph in 1877, thus completely changing the way people were able to enjoy music entertainment at home. Hoping to provide a visual accompaniment to the phonograph, Edison tasked his young lab assistant, the Scottish inventor William K. Dickson, to invent a motion picture camera. That camera was called the Kinetograph.

Because Edison intended for his motion picture device to be accompaniment to his phonograph, he did not envision movies as a communal viewing experience; instead, he asked Dickson to design a peephole viewing device, called the Kinetoscope, which was battery driven and ended up weighing more than 453 kg. Starting in 1894, Kinetoscopes were marketed commercially to be installed in places like penny arcades, hotel lobbies, amusement parks, and other spaces. At the same time, the Edison Company established its own Kinetograph studio to create films for the contraption. Initially, the studio produced in-studio films, where circus and vaudeville acts were brought into the studio to perform in front of a stationary camera.

Although he would later attempt to rule the domestic market with an iron fist, Edison decided not to file for international patents on both the camera and the viewing device. As a result, the devices were widely and legally copied throughout Europe, where they were modified and improved upon. It would be the Lumière brothers who would be the first to present moving pictures to a paying audience—and thus give birth to the cinema.

A 1984 Kinetoscope exhibition in Paris inspired the Lumière brothers to invent the first commercially viable projector in 1895. Their device was called the Cinematograph, which functioned as both a camera and a projector. Compared to the Kinetoscope, the Cinematograph was hand-cranked and lightweight at less than 9 kg—and thus relatively portable. While Edison’s company initially shot in-studio motion pictures of circus acts and the like, the Lumière brothers made documentary films, called “actualities", which were shot outdoors on location. They also sent their cameramen all over the world to capture exotic subjects, and in the process introduced cinematic technology to places as far-ranging as Russia, Australia, and Japan. At the time, both Edison’s and the Lumière brothers’ motion pictures were comprised of a single, unedited shot, with no real narrative to speak of. For audiences, their interest stemmed more from the technology than the content of the films themselves.

In 1985, the Lumière brothers started to conduct screenings of their actualities in Paris. Among the audience for a particular December demonstration was the French illusionist Georges Melies. Melies, who ran his own theater, was greatly impressed by the technology and saw potential to create the sort of illusions that could not be done live. He tried to acquire a camera from the brothers to no avail (they wanted to guard their technology, and also believed they were saving him from going down a path with no commercial potential); undeterred, Melies obtained an Animatograph projector in England, and modified it to also function as a camera. In 1897, Melies built his own studio, complete with glass-ceiling, and there he built his own sets and had actors perform the scripts he wrote himself. Through that process he began to create films with a narrative. He also pioneered and popularized film techniques that are used to this day, including dissolves (fade-ins and fade-outs), multiple exposures, slow motion, and more.

3.The Biograph Company and the Edison Trust

Before Hollywood became the epicenter of the American film industry, most of the country’s film studios were based on the East Coast, in New Jersey—Thomas Edison's studio included. However, the cold winter months were unsuited for film production, and the companies were in need of a sunny, temperate location to set up their secondary studios.

Between the late 1900s and 1910s, many films studios set up branches in Jacksonville, Florida, which had a mild climate, an exotic feel, and a relatively cheap labor force. The local conservative establishment, however, were opposed to the idea of their city being swept up in the hubbub of filmmaking—car chases, bank robberies, and actors and actresses running around town. A conservative politician was elected mayor in 1917 based on a platform of taming the movie industry, spelling the end of Jacksonville as a film destination.

A number of other factors contributed to the shift to Hollywood. William K. Dickson, the aforementioned inventor of the Kinetoscope, left Thomas Edison’s employ in 1895. He joined inventors Herman Casler and Henry Marvin and businessman Elias Koopman in founding the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company (more commonly known as the Biograph Company) in New Jersey. The company was the first American company devoted entirely to film production and exhibition, and was one of the country’s leading producers of silent films for more than two decades. Its early films were primarily actualities, but competition from Edison and European filmmakers, in addition to advances in film technology, would spur the company to shift to the production of narrative silent films. A young man named D. W. Griffith joined the company in 1908 as a writer and actor, but would become its principal director within several months.

In 1910, Griffith and his team traveled to Los Angeles in order to shoot a silent film about Native Americans in authentic locations. After setting up a small local facility, the group went a little further north to a small village called Hollywood as part of their location scouting. Griffith was charmed by the beautiful floral scenery and the friendly residents, and he subsequently returned to the area a number of times, and even made the first ever film shot in Hollywood—a short melodrama called In Old California. Rumors of Hollywood, in addition to Griffith’s film, would lead a number of East Coast film studios to head west. Their exodus was also motivated by their desire to escape the iron fist of Thomas Edison.

At the time, Edison owned most of the major U.S. patents relating to motion picture cameras, and frequently filed patent lawsuits against his domestic competitors—crippling the American film industry as a result. In the early 1900s, the industry was dominated by two studios: the Edison Manufacturing Company and the Biograph Company. Edison’s competitors, utterly defeated, approached him in 1907 to negotiate a licensing agreement. Edison, hoping to squeeze his main competitor out of the market, excluded the Biograph Company from the agreement. The Biography Company, in turn, retaliated by purchasing the patent to a technology called the Latham film loop, which was an important feature of virtually all motion picture cameras that were then in use.

Edison sued in order to gain control of the patent, but lost, and in 1908 the two parties began negotiations. This led to the creation of the Motion Picture Patents Company (MPPC), also known as the Edison Trust. The trust included all of the major U.S. film companies, and even local branches of foreign companies like the Star Film Company—the studio run by Georges Méliès. It effectively put the entire American film industry under Edison’s purview.

Many independent film studios and filmmakers responded by moving their operations to Hollywood. There they continued to produce their films for a growing domestic market. The distance made it difficult for the MPPC to enforce its patents, and as the independent filmmakers grew their operations, it became increasingly difficult for the MPPC to file patent claims quickly enough to stop their activities. The MPPC’s authority gradually went into decline, and in October 1915 a federal court decision in United States v. Motion Picture Patents Company ruled that the MPPC’s acts were illegal under the Sherman Antitrust Act. The company was dissolved in 1918, and the American film industry would flourish as a result.

The MPPC’s decline was also sped up by the outbreak of World War I in 1914. The MPPC found itself cut off from most of the European market, which had comprised a significant part of its revenue; meanwhile, the independent filmmakers were less affected as they were mostly producing Westerns for domestic audiences. With film production largely shut down in the U.K., France, Germany, and the rest of Europe, Hollywood then found itself with not only a near-monopoly on American leisure time, but a monopoly on filmmaking in general.

4.From Novelty to Entertainment

Speaking of American leisure time, the rise of Hollywood was also the result of movie theaters opening up in cities across the country. Theaters dedicated to the screening of films first appeared in the early 1900s. Until then, motion pictures could only be enjoyed by one person at a time—using a peephole device like Edison’s Kinetoscope—or, in the cases where they were shown in front of a theater audience, motion pictures were just one part of a more elaborate program that included song and dance, magic tricks, and comedy.

The first type of movie theater to take hold nationwide and become commercially successful was the nickelodeon, named after the fact that the price of admission was a nickel (five cents). Most nickelodeons were small storefront spaces with a screen in the back and around 200 hard wooden chairs for the audience. As the films shown were silent, some theaters had a piano or even involved audience sing-alongs. This type of theater quickly became popular starting around 1905, and by 1910 there were as many as 10,000 theaters across the U.S. It is estimated that around 26 million Americans were going to the movies every week during this time.

When motion picture projectors were first developed, audiences initially gathered to marvel at the novelty of the technology. As film studios were established and began releasing more and more films in more and more movie theaters, audiences started showing up for the films themselves. In other words, the novelty factor wore off and the content of films began to matter. During the period when films were still mostly between a minute to a few minutes long, it was the job of the exhibitor to put together a program to keep an audience entertained. As nickelodeons spread across the country, going to the movies became an American pastime . The trend soon arrived in overseas markets.

As nickelodeons flourished, movies evolved—which would, ironically, lead to the nickelodeon’s demise. As competition grew among film studios, they began to produce longer and more narratively complex works in order to set themselves apart. Single-shot films became short films with multiple shots, which then evolved into feature-length films of an hour or more in length. This would coincide with a shift from documentary films and newsreels to narrative films. Longer movies also meant that audiences needed more comfortable facilities, which led to the rise of larger theaters featuring pipe organs—and sometimes even a small orchestra—to accompany a film. Feature films and rising audience numbers would drive up theater prices from a nickel to a dime (ten cents).

Another important factor behind the rise of Hollywood was the establishment of the star system. In the early days of motion pictures, actors were paid by the day and were rarely credited for their work. This was partly because actors who were theatrically trained were embarrassed to appear in a medium they saw as mass entertainment for unsophisticated audiences. In addition, the MPPC did not credit actors as part of its strategy to hold onto control and profits. Independent filmmakers, on the other hand, took the approach of crediting their actors and aggressively promoting them as a way to draw audiences. This would lead to the rise of silent film stars in the 1910s.