1.Booksmart is a Future Classic

Of all the stereotypes depicted in typical Hollywood teen movies from the 80s and 90s, none have had more jokes made at their expense than the nerd/geek. Such characters were depicted as academically excellent but socially awkward—or just plain unsociable—preferring to lose themselves in numbers or computer code or a good book rather than be cast adrift at a party or other social get-together. They wore glasses that were comically unfashionable and clothes that were either several sizes too small or too big. They were bullied and belittled. As love interests they were ignored, dismissed, and humiliated, and only ever “got the girl" or “got the guy" after conniving elaborate schemes or undergoing physical makeovers.

Such stereotypes practically made “book" a four-letter word. Nerd/geek characters, or those that display nerdy or geeky characteristics, are often described as bookworms, bookish, or booksmart. Bookworm was originally a negative term for someone who reads too much, but today it carries more positive connotations, suggesting a person is hungry for knowledge and adventures of the literary variety. Similarly, bookish refers to someone who loves to read or enjoys studying, but it also suggests an over-reliance on knowledge found in books. Then there’s booksmart, a term that is a veiled insult, an admonishment that insinuates a person is academically smart but lacks common sense, full of knowledge attainable from books but without wisdom—or the know-how—to survive the streets.

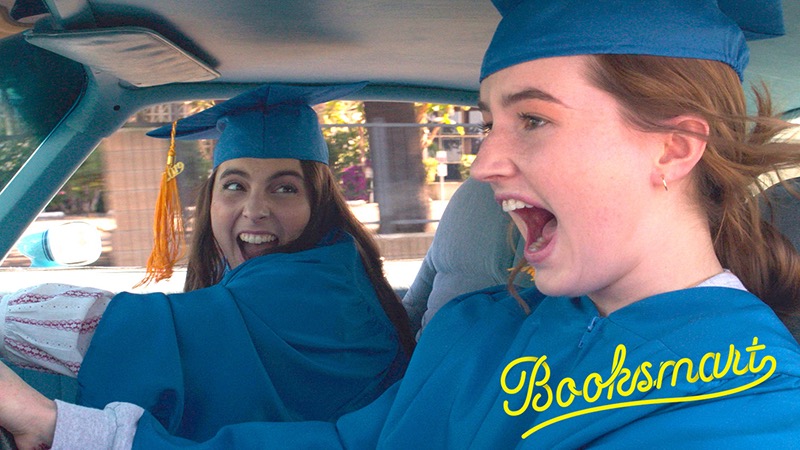

Booksmart, Olivia Wilde’s feature-length directorial debut, redefines what it means to be a nerd in a teen movie in the 21st century. Amy (Kaitlyn Dever) and Molly (Beanie Feldstein), are two nerdy best friends living in L.A. who have dedicated their school lives to academic achievement. They see their relationship to their fun-loving peers as something akin to the fable of “The Ant and the Grasshopper"; they’ve spent their high school years preparing for the future, and believe that their real lives will begin after graduation. When they find out that the classmates they have been condescending to have managed to balance all the fun they were having with academics and sports, and have also gotten into top-tier schools, their entire world is turned upside down. Determined to make up for all the wild times they could have had, they embark on a crosstown quest to make their way to their class’s hottest graduation party—if they can find it.

That all sounds like the recipe for a night full of eccentric characters, awkward encounters, unexpected realizations, and debauchery—and there is certainly plenty of that in Booksmart, which is laugh-out-loud funny from start to finish. But there’s also an abundance of heart, and above all, Wilde’s teen comedy celebrates Amy and Molly’s friendship. The two overachievers share many rituals and inside jokes, such as constantly trying to outdo each other in their effusive praise for their fashion choices, or having a code word that requires the other person to drop everything and show unconditional support, regardless of the reservations they may have. Any friction that does develop between the two of them bubbles up naturally, and stems not from jealousy or mean-spiritedness but from their own insecurities or desire to see the other succeed. In that regard alone Booksmart sets itself apart from other teen movies.

When it comes to teen movies, the story itself is ultimately secondary. There are only so many high school narratives to begin with, and the “high schoolers are suddenly faced with reality as graduation nears" story has been done before. What makes a teen movie a classic—like the John Hughes movies of the 80s—is the characters. The more the filmmakers truly understand where their characters are coming from, the more successful the film. Booksmart, which is filled with memorable, relatable characters and explores the teenage struggle with fondness and respect, deserves to be placed among the classics.

2.The Gen Z High Schoolers of Booksmart

For teenagers, school is where they are exposed to the judgment of their peers, while home is where they are exposed to the judgment of their parents. A teen’s only true sanctuary is their bedroom. (Although the ubiquity of smartphones has rendered even bedrooms vulnerable to outside influence.) It’s where they can fully express themselves without fear or anxiety, filling their space up with their favorite things, adorning their walls and ceilings with posters and art that represent what they are about or what they aspire to be.

If you want to know if a teen movie is worth watching, pay attention to how much care is put into decorating the protagonist’s bedroom—a quick glance should be enough to tell you who they are. The more lived-in the room feels, the more fleshed out you can bet the characterization is. Whether it’s the new wave posters and flags that hang on Ferris’s walls in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off or Cher’s to-die-for walk-in closet in her Beverly Hills mansion in Clueless, a character’s room is about more than eye-catching set decor—it’s a microcosm of their identity. If a teen’s room feels sterile, assume the characterization is razor-thin or disingenuous. (Movies like The Breakfast Club, which take place entirely at school, are an exception.)

The feminist imagery that fills Amy and Molly’s bedrooms in Booksmart tells us everything we need to know about the two Gen Zers. The movie opens with Molly, sitting on the floor of her room with her legs crossed, bathing in the morning light that seeps through her curtains as she meditates to girl-power affirmations. Sitting atop her dresser is a number of academic awards and pictures of former FLOTUS Michelle Obama and the Notorious R.B.G—Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Hanging on her mirror is her valedictorian gown. Molly is—no surprise—class president, a role she takes so seriously that even the school principal thinks she’s overeager.

Amy’s bedroom has floral print wallpaper covered with activist slogans like “My Body My Choice" (after graduation, Amy plans to spend a year in Botswana doing humanitarian work and helping make tampons for women) and “Black Lives Matter", and posters of Jane Austen and Billie Holiday. Although she is an only child, she has bunk beds, presumably so that Molly can sleepover anytime. Amy is a lesbian, and it’s notable that the film does not depict her as anxious about her sexual orientation; she is shown as having come out of the closet several years before the events of the movie, and her parents, who are deeply religious, are also incredibly supportive of who she is.

As their rooms suggest, Amy and Molly share very little in common with the stereotypical nerds and geeks depicted in the teen movies of the past. They come across as real, three-dimensional young women coming of age in a post #MeToo world. The same can be said about their classmates, a colorful and diverse bunch who do not fall into familiar archetypes like the jock and the queen bee.

For example, the popular and pretty Annabelle (Molly Gordon) scored high on her SATs but struggles with a reputation for being sexually promiscuous; long-haired stoner Theo (Eduardo Franco) has flunked a couple of grades in the past but has secured a job at a major ICT company right out of high school; skateboarder Tanner (Nico Hiraga) is bro culture incarnate but muses that the reason he finds Molly unattractive is not because of her looks, but because of her personality; cool girl Hope (Diana Silvers) is quick to make mean comments about Amy’s awkwardness and reservedness, but instead of being depicted as a vain cheerleader, she is more of an edgy loner along the lines of John Bender from The Breakfast Club.

In fact, if anybody in Booksmart is guilty of indulging in stereotypes, it’s Amy and Molly, who are all about women’s empowerment (Amy’s car has a bumper sticker that reads “Still a Nasty Woman”), but only see their peers in the “simplest terms” and the “most convenient definitions”. It’s a pointed criticism of the hypocrisy that is often harbored by those who profess to be the most liberal-minded.

3.Olivia Wilde Shines in Her Feature-Length Directorial Debut

Olivia Wilde has overcome her share of stereotyping and pigeonholing to arrive with her first feature-length directorial debut.

Born in New York to journalist parents, Wilde attended private school in Washington, D.C. and the Phillips Academy boarding school in Massachusetts before deferring her college enrollment to pursue acting. In her early career she became known for sexualized supporting roles in TV shows like the teen drama series The O.C. and the medical drama House.

Wilde became known as a movie actor after playing leading ladies of otherworldly beauty in 2010’s Tron: Legacy and 2011’s Cowboys & Aliens, which were ambitious in scale but only modest successes at the box office. In the ensuing years she continued to build her resume with roles in well-reviewed independent films like Drinking Buddies (2013) and Meadowland (2015), while gradually also taking on more producer roles.

In 2016 she appeared in Vinyl, a HBO TV drama series about the New York rock ’n’ roll scene in the 1970s co-created by people like Mick Jagger and Martin Scorsese. The series was praised for its period accuracy but ultimately did not connect with audiences, and was canceled after one season. Meanwhile, Wilde also received praise for her work directing the “Dark Necessities" music video for the L.A. alternative funk rock band the Red Hot Chili Peppers. The video, which follows four female longboarders as they skate around a deserted L.A., demonstrated a knack for visual style that Wilde fully realizes in Booksmart.

Booksmart is not just a culmination of Wilde’s Hollywood career thus far—it is also the result of her realizing a filmmaking environment that nurtures and celebrates women. In addition to its director and its two stars, the movie’s script was co-written by four women: Emily Halpern, Sarah Haskins, Susanna Fogel, and Katie Silberman. Unlike the overt male gaze of so many teen movies in the 80s and 90s, the writers of this movie have created a portrait of modern female teenagedom from the woman’s perspective.

Their script is brought to life through performances and dialogue that feel natural, genuine, and heartfelt. That Wilde was able to draw such performances out of her actors is a testament to her own sensitivity as an actor and to all the lessons she has learned on set that have shaped her passion as a filmmaker. Taking a note from Scorsese, she banned her actors from bringing scripts and sides to the set, ensuring that they were on top of their game, but also fostering a natural tension and excitement that is part and parcel of the high school experience.

What’s more, much like Scorsese captured the dark, sinister side of New York in movies like Mean Street, Wilde has captured the colorful eccentricity of Los Angeles in Booksmart. The only thing that feels off is the almost complete lack of traffic on the movie’s L.A. streets; then again, teenagers are often so engrossed in their own worlds that they fail to see the world around them.

4.The Evolution of American Teen Movies

In the 70s, teen movies were tales of nostalgia for an earlier age of innocence (for the first half of the decade, the U.S. had been embroiled in the Vietnam War), a trend that would lead to a series of teen sex comedies in the 80s about horny teenage boys who equated losing their virginity to becoming an adult. Meanwhile, directors like Cameron Crowe, who wrote Fast Times at Ridgemont High and directed Say Anything, and John Hughes, with seminal films like The Breakfast Club (1985) and Pretty in Pink (1986), presented a more honest exploration of teenage angst, recognizing that for teens, the world of high school was everything. Their films would usher in the golden age of the teen film, where movies began to take teenagers seriously as a demographic. That being said, even Crowe and Hughes films are mostly centered on middle-class whites, and, like the nostalgia trips of the 70s, can be seen to varying degrees as attempts by the director to relive their own adolescence.

In the 90s, teen movies doubled down on the male gaze fantasies, with movies like American Pie (1999) and She’s All That (1999). At the same time, movies like Clueless (1995) and 10 Things I Hate About You (1999) featured female leads—albeit leads that put on a brave face but were actually lonely, and only felt complete after finding themselves a worthy male suitor. What’s more, these movies also further reinforced the high school caste system and all the stereotypes that entailed. The nostalgia trips also continued, with movies like Richard Linklater’s Dazed and Confused (1993), which takes place at a Texas high school in 1976.

The early 2000s saw the release of more female-centric teen comedies, including Bring it On (2000), The Princess Diaries (2001), and Mean Girls (2004). Many of these films were either written or co-written by women, and made to appeal to a female demographic. Then in the late 2000s, movies like Judd Apatow’s Superbad (2007) would usher in the era of the bromance and brutally honest comedies geared for male audiences. When superhero movies exploded soon thereafter, female teenage audiences were effectively pushed to the sidelines by mainstream Hollywood.

The 2010s would finally see the arrival of teen movies that championed three-dimensional female characters without alienating the teen male demographic. This new wave included Kelly Fremon Craig’s The Edge of Seventeen (2016), Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird (2017), Bo Burnham’s Eighth Grade (2018), and now, Olivia Wilde’s Booksmart. Wilde’s movie is a teen comedy with dramatic elements, an homage to the classic teen movies of the 80s and 90s that also makes you excited about where the teen movie genre might go in the years to come.

5.Epilogue

Although American teen movies have continually evolved and adapted to reflect the times and changing demographics, There is an element that almost all of them share in common: a contradiction between the individualistic “just be yourself" message and the unforgiving school hierarchy (most clearly demonstrated in scenes set in school cafeterias.) depicted therein. While it may not be by design, most American coming-of-age tales set in school are guilty of perpetuating stereotypes and indoctrinating the youth of America into this caste system.

Whether its a movie from the 80s or one from the 2000s, whether it presents the male gaze or the female gaze, all American teen movies are, more or less, about the idea that by cultivating your individuality and proudly letting the world know who you are, everything will work out. The message is that whether you are teased, bullied, or rejected by your peers, you should stand your ground until people have no choice but to recognize and respect you. To put it another way, coming of age is about not letting society destroy your individuality. If you feel like there’s no place for you in society, or that your parents and your classmates don’t accept or understand you, it’s because there’s something wrong with them—something wrong with society. Be yourself, these movies argue, and people will eventually come around. But while the idea that everybody is gifted is ridiculous, the fact of the matter is that the only way to make it in America is to be utterly convinced that you are, in fact, special. The chasm between this unfounded self-belief and reality is partly why there’s so much unhappiness in American society.

If American teen movies wholeheartedly believed in the message they were attempting to sell, they would be about dismantling the school caste system—or at the idea that doggedly championing your individuality will allow you to transcend the hierarchy. But instead, they reinforce stereotypes by giving few characters any true depth. And they are too often vehicles for male directors who were unable to transcend said hierarchy to refashion their past into their glory days. It’s even worse for female protagonists, who often have to undergo physical makeovers in order to discover their “true" beauty.

Booksmart argues for another way—that teen movies have the choice of simply not treating the caste system as a fact of life. Over the course of the movie, Amy and Molly realize that it isn’t their classmates’ fault for not recognizing that they are both “smart and fun". Rather, it’s that they didn’t bother to get to know their classmates. We as the audience make a similar realization: the two protagonists are not just booksmart overachievers, but funny, brave, scared, resourceful, mature, and childish all at the same time.

Booksmart also suggests that the “just be yourself" maxim no longer holds true for Americans; perhaps it never did. Amy and Molly want to party for one night not so they have no regrets, but rather to demonstrate to their classmates that they are “fun". Their main concern is how they are seen by their peers—something that is compounded by the ubiquity of social media. While they still have some growing up to do, I’d argue that a healthy awareness and concern about how others perceive us is a sign of maturity—an acknowledgement that we need society just as much as society needs our special gift. Then again, there’s Donald Trump, the holder of the biggest—and most fragile—ego in the world, whose chief preoccupation as president seems to be to obsess, fret, and whine over what other people think of him.

It’d be a disservice to what Wilde has accomplished with her directorial debut to categorize Booksmart as just another teen movie, because it has so much more to offer.