1.Prologue

Since the final episode of Sekai e Hasshin! SNS Eigojutsu aired on March 19th, I’ve had time to reflect on my time on the show. There has been so much I’ve learned and come to realize over the past two years, and I’m truly grateful for what’s been an invaluable experience.

Getting to observe Torikai Kumiko-sensei tackle the major challenge that is English education reform in Japan has been incredibly eye-opening and humbling. On our show we often highlighted the kind of hip, current English expressions that other Japanese shows wouldn’t dare feature, and it was very rewarding to get to introduce our audience to the English being used by young people today. While I often felt that I could talk about particular expressions at length, in practice my commentary was usually edited down to a concise minimum. While that may make for entertaining TV, the problem is that cursory descriptions of complicated, nuanced expressions leave viewers with an incomplete understanding—which in turn could one day result in a gaffe or critical blunder in an otherwise innocuous discussion or email with, say, a foreign client. Even when it came to the kind of casual expressions thrown about by young Americans in daily life, carelessly drawing my costars’ attention to colloquialisms they didn’t necessarily need to know could have spawned a potential “Oh my God!" type situation—where viewers around Japan are inspired to start reacting to every little thing by invoking the name of the Creator.

Watching Ms. Torikai put the utmost care and consideration into the expressions she highlighted on the show made me think long and hard about what kind of English language education would be truly helpful for the Japanese, and what my role should be as a native speaker of English.

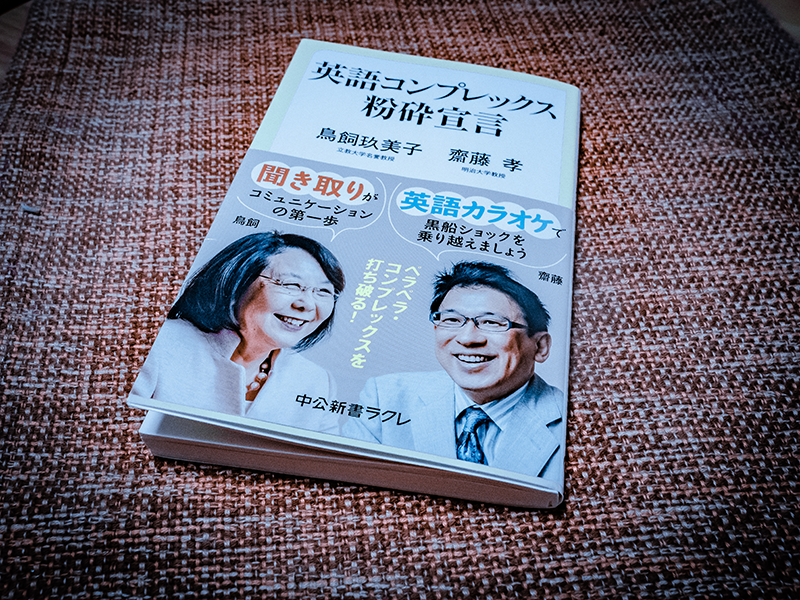

This week I will be reviewing the new book Eigo Kompurekkusu Funsai Sengen (英語コンプレックス粉砕宣言), which compiles a series of conversations between Ms. Torikai and Meiji University professor Saito Takashi for the monthly opinion magazine Chuo Kouron. Their conversation begins with the impending changes to Japan’s standardized university entrance exams and the delay in the implementation of private-sector English proficiency tests. From there, they cover a range of topics, including why the Japanese are so obsessed with English, how the focus of English education should differ across elementary school, middle school, and high school, and low-pressure ways to use English in everyday life. Both are passionate and highly knowledgeable throughout, and more importantly, they always come around to constructive suggestions for a brighter future. Viewers of Sekai e Hasshin! SNS Eigojutsu will even get a few behind-the-scenes anecdotes from the show!

2.The Language Inferiority Complex

About 15 years ago, when I was a college student studying abroad in Japan, I didn’t know what to make of all the eikaiwa (English conversation) schools I saw around town. In the U.S., we had things like Japanese language schools, or Spanish conversation class, or a French conversation study group. I had never seen a school that focused exclusively on conversation in a certain language. That was the first time I realized that all of Japan had a major inferiority complex regarding the English language.

The authors explain that speaking skills are already the focus of English language education at most universities in Japan. In recent years, this predilection has begun to spread into secondary education, and even primary education. When learning English (or any other second language, for that matter) there are four major skills that a learner needs to master: listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Each of these feed into one another, and a comprehensive approach is key. Yet so many Japanese are concerned first and foremost with their speaking skills. Usually, their obsession is the result of some traumatic language experience, such as being asked for directions on the street by an English language speaker, or being unable to join in on a conversation at a party.

For Americans (specifically American men), offering one’s opinion in no uncertain terms is the surest way to command a room; they live for it. For Japanese speakers placed into such a situation as an outsider, it’s understandable that they would become desperate to get in a word edgewise and thus have their presence validated. Unlike in Japan, they cannot rely on their companions to indulge them (amaeru) when they look lost.

According to Ms. Torikai, reading skills form the foundation for success when it comes to second language mastery. Reading skills form the basis for listening and writing skills, and speaking skills come last—only as robust as the foundation under it. Businesspeople who work on the international stage need to be able to read and write e-mails and contracts; similarly, scholars and researchers must be able to read and write academic papers and essays. In other words, even Japanese speakers who ostensibly use English every day generally do not need to speak the language daily. In fact, Mr. Saito takes it one step further by saying that he suspects that less than 1% of the Japanese population truly need English skills in daily life. Yet so many Japanese people are under the misapprehension that they must be able to speak English.

In recent years there has been no shortage of easy learning methods and teaching materials on the market that claim they can foster English mastery with minimal effort. Ms. Torikai points out that there has been a shift in messaging with such products from “learning English" to “acquiring English with as little effort as possible". It should go without saying that mastering a second language requires a herculean effort. The theory has perhaps been overplayed at this point, but take Canadian journalist Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000-hour rule—the idea that the key to mastering a skill is practicing for 10,000 hours—which he put forth in his 2008 book Outliers. Let’s apply this rule, for the sake of argument, to English language acquisition. If you were to move to the U.S. and fully immerse yourself in the English language for eight hours a day, it would take you three-and-a-half years to reach 10,000 hours. If you were a first grader who resolved to study English for two hours a day, it would take you 13 years. This is an oversimplification, but nevertheless, it suggests that the only way to language mastery is hard work and perseverance. As Mr. Saito says, whether it’s language or any other subject, “You have to seize it yourself. You need to be prepared to scale the boulder." (p.39) Yet the majority of Japanese aren’t willing to go through the blood, sweat, and tears, instead choosing to focus their energy on lamenting their inability to speak English and blaming the education system for their misfortune.

Mr. Saito comments, “That you would be so fixated on English despite the fact that you have a mother tongue...in a sense, it’s like the woe of a colonized people." (p.58) Really, the fact that the Japanese are so quick to neglect their mother tongue in the blind pursuit of English conversational mastery is tantamount to self-colonization. The argument for this pursuit is that it will help Japan attain some “global standard". However, the authors point out that this is a crucial mistake, as what so many Japanese assume is a global standard is in actuality nothing more than an American standard.

Japan has harbored an inferiority complex toward the U.S. ever since the end of World War II. In that sense, it’s not that the Japanese are obsessed with the idea of speaking English; rather, at its core, it is a desire to be acknowledged by the U.S., to be like the U.S. Some have said that the start of the Reiwa era should serve as a bookend of sorts to the postwar period. But until the Japanese are able to leave their feelings of inferiority behind, the postwar era will never be truly over.

This book offers many different ideas for pulverizing that language inferiority complex into oblivion.

3.How to Overcome a Language Inferiority Complex

One of the conclusions that Ms. Torikai and Mr. Saito come to is that if elementary school students in Japan are going to be taught English, you might as well take it as an opportunity to condition them be more comfortable with the language and less obsessed with learning how to speak it. Then, free of the shackles of inferiority, students can be taught grammar in middle school, and then learn how to read, write, and talk about meaningful, intelligent things in high school. This is the general framework for English language education that they propose. In grade school, students would read excerpts of English-language classics aloud in order to become familiar with the sounds of the language and get over any pronunciation trauma.

As I mentioned earlier, Mr. Saito conducts research into the development and implementation of body-based educational methods, and one of his theories has to do with the concept of shin-gi-tai (心技体)—an expression commonly used in sports and martial arts that refers to the joining of mind, technique, and body to create a complete person. The idea is that a person is able to tap into their full power when there is a balance and harmony between their spirit, skill, and physical strength. Mr. Saito believes that of the three elements, the body forms the foundation. What this all means is that Mr. Saito takes a unique, comprehensive approach to conquering language. Throughout the book, he proposes a number of intriguing out-of-the-box ideas for studying English and overcoming a language inferiority complex.

One of those ideas is to practice pronunciation by singing English-language songs karaoke-style. Japanese people love karaoke, and regardless of how good or bad a person’s English pronunciation is, they will always try valiantly to do English-language songs justice. As Mr. Saito notes, “The stress on the English words is synced up to the notes of the music, so singing it allows you to learn English pronunciation and rhythm." (p.85)

So what is Mr. Saito’s go-to karaoke tune? It turns out he is quite fond of Queen’s “I Was Born to Love You". This song, originally a tune on Freddie Mercury’s solo album, became a big hit in japan after it was chosen as the theme song of Pride, a popular TV drama starring Kimura Takuya. (Queen has always been big in Japan—bigger than it ever was in both Europe and the U.S.) The lyrics are simple, and the words “born" and “love" give karaoke-goers the perfect chance to work on their l’s and r’s. For these reasons, he even suggests that it would be perfect for grade schoolers. On this point, I have to object, as the lyrics contain the following passage:

You are the one for me

I am the man for you

You were made for me

You’re my ecstasy

If I was given every opportunity

I’d kill for your love

Ecstasy, of course, is a hallucinogen, and Freddie seems oddly serious when he proclaims that he would “kill for your love”. And the phrase “If I was given every opportunity” is nonstandard and ambiguous.

Nevertheless, I believe this karaoke method could work wonders not just for grade schoolers but also for adults and those who hope to become an English teacher. For the past few weeks now the world has been self-isolating and cooped up indoors due to COVID-19; may I suggest hopping onto YouTube and searching for the karaoke version of your favorite song?

Ms. Torikai proposes using the children’s story Swimmy, which all Japanese schoolchildren read in the second grade. Her idea is that students would read the Japanese version in second grade, and then the English version in fifth grade. Swimmy was originally a picture book by the Jewish illustrator of children’s books Leo Lionni, who was born in the Netherlands and raised in Italy. It is the story of a small black fish that stands out because he is a different color from his otherwise red school. When he is forced away from his home, he embarks on a journey of self-discovery. The story actually reflects the struggles of Lionni himself, who fled to America to escape the Mussolini regime, and later returned to Italy after World War II came to a close.

I also read Swimmy during second grade at my Japanese language school in California. My teacher at the time explained to us that the message behind the story was “Even if you are weak individually, if you combine your strength, you can overcome any obstacle. I remember feeling perplexed, because to me it was clear that the story was about a special fish that had embarked on a hero’s journey, returned as a leader, and helped defeat a powerful enemy. The experience opened my eyes to the fact that Japanese society is not about the individual but about the collective.

Ms. Torikai suggests Swimmy would thus expose elementary school students to cultural differences between Japan and the West. Reading the same story in both Japanese and English is something I have done many times in the past and continue to do to this day. It is a very effective way to study English (and Japanese).

4.Language Drills and the Limits of a Native Speaker’s Usefulness

One highlight of the book is Mr. Saito’s penchant for interesting sports metaphors. A former coach at a tennis school, he characterizes the fact that English classes at Japanese schools mostly consist of the teacher talking and the students listening as follows: “They don’t hit the ball back. In sports, it’s important to get in as many ‘reps’ as you can. The same can be said for studying." (p.41) Later in the book, he compares learning grammar to “taking practice swings", and reading example sentences aloud to “hitting a live ball and getting a feel for it". He stresses the importance of repetition when you’re goal is to get an intuitive feel for a language.

On this, the two authors disagree. Mr. Saito sees the dislike among students for English-language training and drills as a negative, while Ms. Torikai—who admits that she’s never really done any sports-related training herself—has reservations about making grade school children memorize even more things through repetition. I can understand where she’s coming from. After all, the word “drill" is originally a military term meaning “the act or exercise of training soldiers in marching and in executing prescribed movements with a weapon" (Merriam-Webster). I’d have reservations about having grade school children do drills, too—especially given Japan’s past and pacifist nature.

That being said, both agree that just because you’re a great professional tennis player doesn’t mean that you’ll make a great tennis coach. (In fact, it’s often the middling pro players that make the greatest coaches. A few examples include Brad Gilbert, who coached Andre Agassi; Darren Cahill, who coaches Simona Halep and also previously coached Agassi; and Sascha Bajin, former coach of Osaka Naomi.) Similarly, the two acknowledge that just because you’re a native speaker doesn’t mean you’ll make a great English language teacher.

Admittedly, that was a little difficult for me to hear. On Sekai E Hasshin! SNS Eigojutsu, our MC Haruhi-san and co-hosts Hide-san and Gori-san would frequently ask me about how to pronounce a word. All I could do was point idly at my mouth and enunciate—maybe say something a little slower than I normally would. I had no idea how to explain the technical movements of the tongue and jaw in English speech. Meanwhile, Ms. Torikai, who has studied phonetics, was always able to explain how a word should be pronounced. When our co-stars finally—inevitably—got it right, the look of accomplishment on their faces said it all.

The limits of a native speaker’s powers also became painfully apparent to me when I started doing translations. As someone who was born and raised in the U.S., I’d never truly learned English grammar at any point in school—my grammar instincts had all been acquired through osmosis. I’d developed my sense of what sounded “right" and “wrong" through daily conversation and reading many, many books.

After I came to Japan and started doing Japanese to English translations, I was heartened to find that clients that were either fluent in English or knew no English at all were both receptive to my translations, save for some minor adjustments in nuance or tone. But then, a certain client that was under the misapprehension that they could speak passable conversational English got back to me with a ton of feedback—not about content, but about grammar. The comments were off the mark and misguided, and it was clear to me that the client was in the wrong. But I was at a loss as to how to express to them in grammatical terms what I knew instinctively. Following that experience, I decided I had to relearn grammar from square one. Especially helpful were books like Grammar for Middle School Students by Tsukuba University professor Ikenaga Katsumasa, and Translation from English to Japanese by Nakahara Michiyoshi.

5.To Say Something Meaningful in English, You Need to be Able to Say Something Meaningful in Japanese

In the second half of the book, Mr. Saito and Ms. Torikai talk about the pleasure of translating difficult English passages.

As I mentioned above, the general framework the pair have put forth is as follows: become familiar with the sound of English in elementary school, learn grammar in middle school, and become able to have meaningful, intelligent discussions in high school. In order to say something meaningful, you have to be able to write something meaningful; in order to write something meaningful, you need to be able to read something meaningful. To that end, the authors recommend reading, breaking down, and translating passages from notable English-language intellectuals and authors.

Mr. Saito says that in order to properly interpret a difficult passage, you must simultaneously approach it from two directions: sentence structure and context. Ms. Torikai, however, laments that she has observed that students “disregard structure and context, and instead simply look up what words mean in the dictionary and string together the translations that they happen to come across." (p.150)

As a result, the Japanese translations the students produce hardly make any sense as Japanese sentences—like something you’d expect from an internet search engine translation. The authors, at last, come to the heart of the matter: students’ obliviousness to the incoherence of their own Japanese translations suggests a lack of Japanese skills. After all, what you can’t say in your native tongue, you can’t say in a second language.

What accounts for this decline in the Japanese language? Mr. Saito argues that it is because of education reforms that were implemented after World War II came to an end. Losing the war had left Japan with both physical and emotional scars, and an inferiority complex not only toward the English language but also toward all things American—and even the Japanese language itself.

In turns out that in the postwar period, in the country’s rush to reject its prewar history and thought—the things that led it to war in the first place—it threw the baby out with the bath water. The English language was logical, and thus superior. The Japanese language was too sentimental, and thus inferior. By extension, modern Japanese literature—which has since become celebrated around the world—was also seen as too sentimental and not based on logic. Today, passages from famous authors like Natsume Soseki and Akutagawa Ryunosuke are beginning to disappear from Japanese language textbooks, replaced by straightforward, descriptive sentences written specifically for use in textbooks.

Ultimately, Ms. Torikai and Mr. Saito come to the conclusion that the key to casting off the shackles of the postwar era and preventing the self-colonization of Japan is to protect the Japanese language. It is to revive an appreciation for the depth of the country’s mother tongue. Japanese people should stop feeling embarrassed about being unable to join in on party conversations or give directions in English. That being said, if a foreigner interested in Japanese culture asks you a question about modern Japanese literature, and you find that you are unable to put together a coherent answer even in Japanese, that is something to be concerned about.