1.Prologue

At the outset of the 1960s, America was brimming with optimism. In 1961, John F. Kennedy became president, serving as a beacon of hope for a generation coming of age as well as African-Americans and other minorities. The civil rights movement was in full swing, as was student activism in the form of anti-Vietnam War protests and other campaigns. In the second half of the 60s, the hippie movement came into full bloom, championing alternative lifestyles and a philosophy of “Love & Peace". Many people believed wholeheartedly that society was undergoing a major change for the better.

Despite the sunniness of the era, racism remained very present in almost every aspect of daily American life, and music was no exception. Hippie idealism was mostly the domain of young white Americans, while the civil rights movement was chiefly an African-American struggle. White Americans listened to white music—rock—while black Americans listened to black music—soul. White radio mostly refused to play black music, and vice versa.

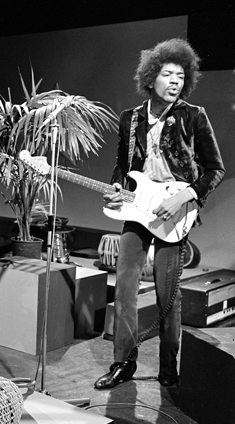

There were exceptions, however. Some black musicians were inspired by Jimi Hendrix’s guitar playing and began incorporating psychedelic influences into their music. Others broke through on the Billboard pop charts and achieved crossover success. Some achieved both. They combined white psychedelic rock with black soul, added a healthy dose of hippie optimism and balanced it all out with social awareness to create a new genre of music that would come to be known as funk.

In this piece I will look back at the dizzying heights reached by those black artists.

2.The Psychedelic Soul of Sly and the Family Stone

In the 1960s, mainstream black music was soul music—songs about love performed by all-male vocal groups in tuxedos and all-female vocal groups sporting identical hairstyles.

In that sense, Sly and the Family Stone was an outlier. The mixed-race and mixed-gender band formed in the hippie mecca that was the San Francisco bay are stood apart from the pack for many reasons—their colorful costumes, multiple lead singers, and female performers who played instruments. Their sound was a blend of soul, rock and roll, and psychedelic music. At a time when a deep chasm existed between “white" and “black" music, Sly and the Family Stone embodied the utopian ideals of the hippie movement better than any band.

The band released its debut album in 1968 but its idiosyncratic sound was met with little fanfare. In response, the band’s record company pushed it to produce something more commercial; Sly himself recognized that in order to get the band’s progressive message out into the world to regular listeners, they needed to break through on the music charts. Their answer was the top 10 single “Dance to the Music", a seminal song in the development of the psychedelic soul genre.

The song featured rock-flavored guitar and soul-infused bass, jazz-influenced scatting, and half-sung, half-spoken vocals—a perfect encapsulation of the band’s magic. The playful lyrics introduce each member of the band, emphasizing its message of individuality and unity. For Sly’s self-introduction, he invokes soul singer Wilson Pickett’s “Mustang Sally" with his passionate call “Ride, Sally, ride."

Sly and the Family Stone’s psychedelic soul masterpiece was its fourth studio album, Stand! (1969). The album’s most well-known song is the hippie anthem “Everyday People”, a song about diversity—how we can all live in peace and harmony. Here are the lyrics to the first bridge:

Stand!

Sly and the Family Stone’s fourth studio album was released in 1969. Rolling Stone magazine ranked it 121st on its list of the “500 Greatest Albums of All Time”.

There is a blue one who can't accept the green one

For living with a fat one, trying to be a skinny one

And different strokes for different folks

And so on and so on and scooby dooby doo-bee

This section is sung to the rhythm of the popular playground taunt, “na-na-na-na-na". The phrase “scooby dooby doo" comes from jazz scatting, but it’s interesting to note that in 1969, just a year later, the popular children’s animated TV show “Scooby Doo" would hit the air. In any case, Sly and company are trying to get across the childishness of discrimination and emphasize that we are all just “everyday people".

This album was the band’s true mainstream breakthrough. In August of 1969, the band performed a legendary set at the Woodstock Festival; just a few weeks earlier, it had been the headlining act at the Harlem Cultural Festival (aka “Black Woodstock").

Success, however, brought discord among the band’s members. Members of the Black Panther Party demanded that Sly fire the white members of his band (Martini and Ericco) and hire black musicians instead. When the band moved its base of operations from San Francisco to Los Angeles, its members started regularly using cocaine and other drugs. Drugs took the heaviest toll on Sly, who began acting erratically and didn’t show up for one-third of the dates of the band’s concert tour. Its inner turmoil reflected larger social shifts: Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated, militant groups rose to prominence in the civil rights movement, and the Vietnam War was becoming a quagmire.

The band’s fifth album, There’s a Riot Goin’ On (1971), is a dramatic shift away from the positive vibes of its psychedelic soul predecessor toward a moody, heavy, muted funk sound. Sly wrote and performed most of the album’s music alone, making standout tracks like “Family Affair" an ironic counterstatement to “Everyday People". The lyrics are about the good and bad sides of family, and is characterized by the contrast between Sly’s low funk-styled vocals and his childlike wails toward the end of the song.

There’s a Riot Goin’ On

Sly and the Family Stone’s fifth studio album was released in 1971. Rolling Stone magazine ranked it 99th on its list of the “500 Greatest Albums of All Time”.

The band would continue for a few more years with a number of changes in the lineup, but its drug problems would only worsen, damaging its reputation as a live band. The band would dissolve in 1975.

3.Curtis Mayfield and the Inner City Reality

Curtis Mayfield was born in 1942 in Chicago, Illinois. His father walked out on his family when he was five years old, and he was raised by his mother and grandmother while moving between different projects around the inner city. His mother taught him how to play the piano, and he joined a local gospel group when he was eight years old. He taught himself how to play the guitar when he was around ten. In 1958, Mayfield and other members of various local doo-wop groups came together to form a new group called The Impressions. When the group’s leader left soon thereafter, Mayfield became the de facto leader and began to write a string of gospel-tinged R&B hits for the group and other groups on its label.

From the beginning of his career, Mayfield incorporated his experience with the problems surrounding inner city minorities—crime, poverty, and drug abuse—into his songs, setting The Impressions apart from rival groups such as those from the Motown stable that sang mostly about love. After the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed, outlawing racial discrimination in America, his songs began to embody even stronger political and social statements. Several of The Impressions’ songs from this period became anthems of the civil rights movement. Perhaps the most iconic was 1965’s “People Get Ready", which hit No. 3 on the U.S. R&B chart and No. 14 on the pop chart. Here are the opening lyrics to the song:

*Jeff Beck and Rod Stewart released a great cover of this song in 1985. Stewart was the singer for the Jeff Beck Group in the late 60s, but he the band was dissolved after the two began butting heads; this cover represents a mending of fences, although the pair would stop speaking again for many years afterwards.

*The Japanese city pop artist Yamashita Tatsuro is also known as a diehard fan of Curtis Mayfield, and his song “Soubou" is in many ways a response to the call of “People Get Ready". When playing the song live, Yamashita often slips in a rendition of the soul classic.

People get ready

There's a train a-coming

You don't need no baggage

You just get on board

All you need is faith

To hear the diesel’s humming

Don't need no ticket

You just thank the Lord

The song, which reassures the black community of coming social change, comes from a long tradition of African-American spirituals and freedom songs like “Wade in the Water" and “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot". The train that Mayfield mentions is a reference to the Underground Railroad, a secret network of routes and safe houses used by abolitionists to help slaves escape from the South into the free states of the North and Canada. The train also symbolizes mobility and freedom—both of which African-Americans at the time likely felt that they had not yet truly obtained. Martin Luther King Jr. used the song at events to encourage people to march or to calm and comfort them.

Seeking an outlet for his message that was unencumbered by the inherent limitations of a group dynamic, Mayfield left The Impressions in 1970 and started a solo career. His first single, (Don't Worry) If There's a Hell Below, We're All Going to Go is a powerful warning regarding the fragile state of race relations in America’s inner cities. The song combines elements of psychedelic soul and funk: brass and string instruments, wah-wah guitar, and vocal echo.

Mayfield’s greatest masterpiece is said to be his 1972 movie soundtrack album Super Fly. The movie is about an inner city drug dealer and pimp who is looking to get out of the game. Many African-Americans were against the depiction of black men as pimps or drug dealers or gangsters in movies and TV, but many young black men who had been born during the civil rights movement saw the protagonist’s arc as one of the few ways they would ever be able to rise above the slums and achieve success.

Super Fly

Curtis Mayfield released this soundtrack album in 1972. Rolling Stone magazine ranked it 69th on its list of the “500 Greatest Albums of All Time”.

While the movie is ambivalent about its message, Mayfield’s lyrics are much more straightforward about its anti-drug message and the realities of inner city life. For him, it was up to African-Americans to break themselves out of the downward spiral of the slums and obtain freedom. It is a stark depiction of the effects of the conservative white backlash against the civil rights movement.

4.The Evolution of the Motown Sound

The Temptations were one of the most iconic groups to come out of Motown’s stable in the 1960s. For the first phase of its life up through the mid 60s, it was known among black audiences for its piano and string-backed ballads, like the classic “My Girl".

In 1966, Motown songwriter Norman Whitfield became the band’s chief producer. Whitfield began incorporating James Brown-esque brass sounds and gave the Temptations a harder-edged sound to their soul crooning. Motown also strategically steered the band toward achieving crossover success, and by the late 60s the group had an international reputation. In 1968, Whitfield was inspired by Sly and the Family Stone’s “Dance to the Music", and his psychedelic soul-influenced work would push Motown’s sound in a new direction. The first psychedelic soul single he penned was the Temptations’ “Cloud Nine".

Taking Sly’s lead, the song is not a love song in line with Motown tradition, but rather a song about being poor and black in America. And in contrast to the band’s formation up until that point—where one member sang lead and the others provided backup—the song sees the members trading lead vocal duties. The song was a hit, and won Motown its first Grammy Award for Best Rhythm & Blues Group Performance, Vocal or Instrumental.

Whitfield would continue to employ experimental vocal arrangements, distorted guitar, multi-tracked drums in his songs for the Temptations, and he even began writing songs in a similar vein for other Motown artists.

One of his widely covered pieces is the Motown standard “I Heard it Through the Grapevine". The composition found its greatest success in the arrangement Whitfield made for Marvin Gaye. The slow, deliberate tempo foretells the inevitability of a breakup, a feeling enhanced by the mysterious atmosphere produced by the organ and Gaye’s desperate vocals, which feel like they could break at any moment—Whitfield purposely asked Gaye to sing the song in a higher key than his usual delivery, to great effect.

Another Whitfield-penned tune was the seminal protest song “War", sung by Motown artist Edwin Starr. “War" was originally written for the Temptations, who recorded the song as an album track; label head Berry Gordy was against releasing that version as a single, as he was afraid the Temptation’s more conservative fans would not respond well to the anti-war message. Starr’s angry vocals evoke the rawness of James Brown.

Whitfield’s magnum opus of psychedelic soul—and perhaps the most powerful song in the Temptations oeuvre—is “Papa Was a Rollin’ Stone" (1972). The original version is a dramatic work of cinematic soul that stretches close to 12 minutes long, most of which is comprised of long instrumental passages and orchestral sounds. The seven-minute single version reached No.1 on the U.S. pop charts and No. 5 on the R&B charts. It won the group its second Grammy Award for Best Rhythm & Blues Group Performance, Vocal or Instrumental.

The lyrics are a conversation between sons and their mother; the sons ask their mother about the veracity of the many rumors they’ve heard about their dead father, and the mother answers each time with the same three lines:

Papa was a rollin’ stone

Wherever he laid his hat was his home

And when he died, all he left us was alone

The expression “rolling stone” refers to someone who is unwilling to settle in one place for long, and in the song suggests that the boys’ father likely moved from job to job, from partner to partner, and from home to home. The song is about the fact that so many black Americans grow up without a father.

While the song was a hit, behind the scenes tensions were growing between Whitfield and the members of the Temptations. The group was frustrated with the fact that their producer’s songs were becoming increasingly centered on instrumentals rather than their vocals, as well as the dearth of love songs in their new material. In the mid 70s, Whitfield would leave to establish his own record label.

The Best of the Temptations

This is a two-disc best-of compilation spanning the majority of the band’s classics.