1.A Singular Museum in the Middle of a Quiet Residential Neighborhood

When the Yayoi Kusama Museum opened in fall of 2017 in the Bentencho neighborhood of Shinjuku, Tokyo, fans of the legendary avant-garde artist finally got a place where they could see her work permanently. Following numerous exhibitions at renowned museums around the world, her infinity nets, polka dots, pumpkins, and more have captured the imaginations of contemporary art-lovers and Instagrammers alike. A survey of museum attendance conducted by The Art Newspaper named Kusama the World’s Most Popular Artist in 2014. And in 2016, she received Japan’s Order of Culture, one of the highest honors bestowed by the Imperial Family.

The arrival of the white-walled modernist building was itself a splash of contemporary art in the middle of an otherwise unassuming and unremarkable residential area. Making the most of limited space, the structure is comprised of cubes stacked atop one another, with rounded corners. The individual galleries inside are minimalistic spaces that consist of white walls, high ceilings, and floor-to-ceiling glass windows.

Although located between Waseda University and the upscale Kagurazaka neighborhood, for most the museum will be off the beaten path. There are hardly any other landmarks in the neighborhood, and few cafes or eateries to hang out before or after a visit. With tickets for a set number of slots available exclusively online (no door tickets are available), this is not a place that tourists will stumble across—it is a secluded haven that must be sought out.

The museum’s latest exhibition, I Want You to Look at My Prospects for the Future: Plants and I, which runs until February 28, 2019, is a journey through Kusama’s relationship with plants, botanical imagery, and self-portraits—from sketches she made in her teens, to some of her early works as an avant-garde artist, to selections from her more recent paintings. It showcases 35 of Kusama’s works across five floors, and provides a snapshot of her evolution as an artist, as well as a sensory experience of the themes central to her work.

2.Down the Rabbit Hole

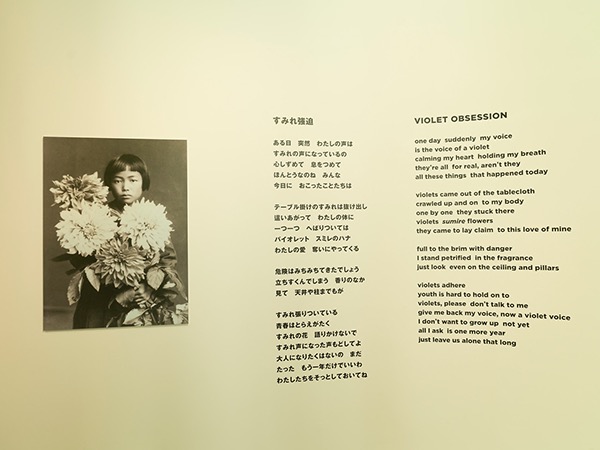

After checking in at the first floor reception desk, visitors can stash their belongings away in a locker and then head up the stairs to the second-floor gallery. There, they are greeted by Kusama’s poetic reflection on childhood, called Violet Obsession, which begins as follows:

one day suddenly my voice

is the voice of a violet

Kusama was born to a family that owned a seed nursery business, and grew up surrounded by seed harvesting grounds. Plants have long been an important part of Kusama’s identity, both as subjects of her art and the frightening figures that terrorize her in the form of hallucinations she has suffered since she was a child.

In the softly-lit space is a number of her early Nihonga works, 70s collages, and later videography. The latter especially is both beautiful and horrifying; one depicts the artist with gerbera flowers around her neck, and in another she appears to be surrounded by sunflowers that seem to be closing in on her. At first glance she appears to be at the mercy of her obsessions, but in the face of the onslaught she does not blink. Instead, she stares back and confronts the hallucinations that plague her.

As visitors exit the second-floor gallery space, they inevitably cast another glance at the poem, which ends as follows:

I don’t want to grow up not yet

all I ask is one more year

just leave us alone that long

The idea of wanting to stay a child may be difficult to relate to for Westerners, where the primary motivator throughout childhood is the unbridled desire to grow up. Our relationship with the world changes as we become an adult—as a child the world happens to us, but as an adult we happen to the world. In Western cultures, being a child represents naiveté, powerlessness, self-centeredness, and adjectives like “childlike" and “childish" are nothing to be proud of, sometimes connoting inappropriateness and even wickedness. Childhood innocence—especially in Western society—is something to grow out of, something that must be shed or lost.

It wasn’t until the 19th century that the concept of a “child" entered the public consciousness and was acknowledged. Up until then, children were small-scale, “mini-adults" who were immature and ill-equipped for heavy physical labor. Theirs was a wicked existence with little value in terms of manpower. However, in agrarian societies based on rice farming, where the work was troublesome but not burdensome, children were an important source of manpower, tasked with helping make ends meet for the family. As a result, children have long been cherished in Japanese society. (This tends to be true for any society that is based on rice farming, i.e., Monsoon Asia.)

Naturally, the Japanese found beauty in the immaturity of childhood—it is their obsession. This is manifested in their appreciation of anime as entertainment for all ages, and their fondness for character-themed merchandise even as adults. Ride the train and you can often see salarymen flipping through manga anthology weeklies (although these days they are often swiping instead). Personally, I’ve always found this aspect of Japanese society perverse and perplexing. But while Kusama’s colorful work—not to mention her persona—is nostalgic and childlike, it is also undoubtedly striking and unapologetic. Bold and unflinching, she makes the case that there is a universal beauty to things that are childlike.

3.Losing Yourself in Art

On the third floor are 15 works from the artist’s ongoing My Eternal Soul series, colorful acrylic expressions of abstraction and figurativeness born across square panels. These works represent the culmination of the various styles and elements that Kusama herself has developed over the years. Taking in each work in the well-lit space is a trippy experience, as if you were peering through a microscope to get an up-close look at slides straight out of Kusama’s inner psyche. In one painting, the repeated motif of a human face in profile resembles a series of musical notes, playing the same note to the same beat on an endless loop.

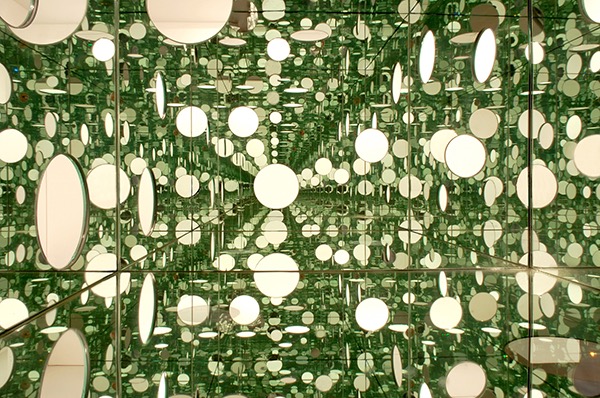

This immersion is amplified by The Passing Winter, a small peep-in mirror room in the center of the space. It has the effect of making the room feel more expansive than it actually is, while simultaneously drawing the observer towards it like a moth to a flame. Peer inside one of the circular holes on the sides, and the observer will see themselves reflected infinitely on the mirrors inside. I was immediately reminded of a mirror ball in the middle of a dance floor, recasting everything in its environment in a new, unceasing light. Kusama’s work exudes the kind of louche vibe that hangs around club culture and the underground.

Speaking of infinity, visitors can experience another world on infinite loop, this time on a larger scale, just upstairs. On the fourth floor is PUMPKINS SCREAMING ABOUT LOVE BEYOND INFINITY, a mirror room produced especially for the museum. Inside, spotted pumpkins flicker in the dark repeatedly, creating the illusion of an infinite pumpkin patch. Although the room features no music, as I stood mesmerized amid the glowing pumpkins, it struck me yet again that the aesthetic would not feel out of place at a nightclub. Much like a darkened dance floor, the dark space channels your focus and your senses into the here and now, where Kusama masterfully opens our eyes to the infinite possibilities that stretch out before us.

This idea of infinity and the recurrence of single motifs is an artistic philosophy that Kusama calls “self-obliteration". For her, it is a form of art therapy, a way to overcome the obsessions and hallucinations that have imposed themselves upon her since childhood. While I do not share her afflictions, I can relate to the comfort she finds in repetition; for me, dance music—specifically the four-on-the-floor variety—has helped me through tough moments in my life, serving as a kind of music therapy.

Unlike pop music and other “conventional" music, dance music is not about the melody so much as it is the recurrence of musical motifs and the unending repetition of a beat. Simply listening to this type of music recreates the feeling of a psychedelic high, a kind of hypnosis. In a setting such as a nightclub, there is a moment when you lose yourself in the music. You lose all sense of self and reality and—as the cliché goes—become one with the universe. For me, music therapy has long been my way of dealing with the trials and tribulations of life; it is where I achieve my self-obliteration.

In her poem that accompanies the fourth floor mirror room, Kusama writes:

I have captured the dignity of such pumpkins and their eternal expression of love towards humanity here in this mirror room.

Much like Campbell soup cans were for pop art icon Andy Warhol, pumpkins are a charming, comical, childlike motif that fascinates Kusama. Through them, she has turned an obsession and her affliction into enchanting, inspiring art. Similarly, a lot of dance music is criticized for blunt, cheesy lyrics or cold, inorganic constitution. But for me, what Kusama shares with the dance music ethos is this expression of love and boundless hope for the future.

4.A Break in the Clouds

On the fifth floor, beyond a small library of books related to the artist’s past exhibition catalogues and novels, sits the last work of the exhibition, Starry Pumpkin, a sculpture covered in pink and gold tiles. On the other end of the open-air space is a bench in front of a window looking out over the surrounding neighborhood, but fittingly, (especially for an introspective artist like Kusama) the most fascinating attraction is the one within the space.

If time allows, I highly encourage visitors to take a moment to sit with your back to the window, taking in the sculpture, which looks as if it might have fallen from the heavens. With white walls, square-tile floor, and the backdrop of sky, the space has the serenity of a zen garden, and is a welcome breath of fresh air after the emotional journey and high that precedes it. Despite being just five floors up, the observer is made to feel as if they are in a “castle in the sky" where the hustle and bustle of the city—along with any worldly concerns—has fallen away; it’s as if you could be on the 50th floor, or the 100th floor.

If the works on the second floor began a journey down the rabbit hole, and the third and fourth floors involved losing yourself on the dance floor of Kusama’s imagination, then the fifth floor is the experience of walking out of the dark club and into the light, emerging from a psychological trip and being rewarded with a fleeting moment of solace. It is in these final moments of the exhibition that you feel like you’ve been freed from the tortured mind of an artist whose creativity knows no mortal bounds. Waiting on the other side is satori—a kind of revelatory experience, a spiritual awakening.

Today, Kusama is one of the world’s leading contemporary artists, and I Want You to Look at My Prospects for the Future: Plants and I clearly shows why. Driven by the urge to create, she boldly confronts and embraces her obsessions and expresses them as only she can. Her art is a guiding light that just might lead all of us out of the darkness and deadlock.

●Exhibition Info

I Want You to Look at My Prospects for the Future: Plants and I

October 4, 2018 – February 28, 2019

●Museum Info

YAYOI KUSAMA MUSEUM

107 Bentencho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, 162-0851

Open:Thursdays to Sundays and national holidays

Closed: Mondays, Tuesdays, and Wednesdays

●Ticket info

Adults:1,000 yen (tax incl.) Children aged 6-18:600 yen (tax incl.)

Visitors must buy tickets in advance. Entry is timed and only valid for a specific 90-minute time-slot.

Tickets go on sale on the museum’s website at 10:00 A.M. (Japan time) on the first day of each month for entry in the month after next.

www.yayoikusamamuseum.jp/

*Door tickets are not available

*Tickets can only be purchased through the museum’s website.

●Visitor Policies

※In the event of inclement weather, the 5th floor may temporarily close.

※Please keep luggage and oversized bags in a locker behind the reception area on the first floor.

※Photography and filming are not allowed except for areas with permission signs. No flash photography or video. No tripods or selfie sticks.

※Please read the full list of policies on the museum website.

https://yayoikusamamuseum.jp/en/visit/policies/