1.Prologue

In my previous entry in our “Famous Books About Japan” series, I covered the intellectual giants of prewar Japan.

In this article I will cover the intellectual giants of postwar Japan. After Japan’s unconditional surrender at the end of World War II, there was an effort to spread the ideals and values of a new postwar democratic order based on Western models, spearheaded by a group of leftist thinkers who came to be known as shinpo-teki bunkajin, or “progressive men of letters”. They were opposed by intellectuals on the right who saw their knee-jerk rejection of prewar and wartime Japanese thought as short-sighted and intellectually disingenuous.

Opinion in postwar Japan was largely defined by ideological debate between the left and the right. In this article I hope to introduce what each of these thinkers believed and argued, how they influenced each other and attempted to elevate the debate for the sake of Japan’s future, and the message they intended for Japanese society at the time—as well as the lessons they still hold for us.

2.Maruyama Masao and the Lack of an Ideological Touchstone in Japanese Society

The first thinker I’d like to bring up is Maruyama Masao, a leading Japanese political scientist and political theorist who was one of the key figures of the movement of “progressive men of letters".

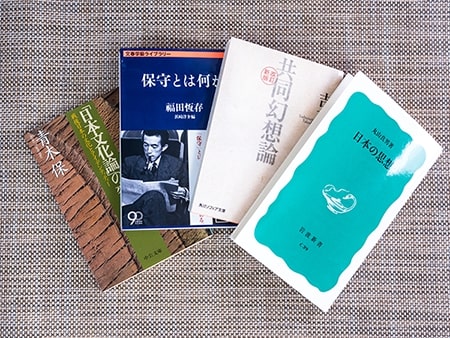

Maruyama’s best-known work is Nihon no Shiso, which has been translated as “An Explication of Japanese Thought". Released as a shinsho paperback in 1961 by the progressive-leaning Japanese publisher Iwanami, it is known for its distinctive green cover design and deceptive thinness. Over the years it has become notorious for being a difficult read for Maruyama’s unique construction and his fondness for citing historical works.

In the foreword, Maruyama argues that while Japan has no shortage of books that put forth theories of Japanese thought and the Japanese spirit, it lacks comprehensive studies of the history of Japanese thought. While there are plenty of books like Doi Takeo’s The Anatomy of Dependence—which I will cover later in this article—those books focus on specific aspects of Japanese society and do not attempt to establish a framework for understanding Japanese thought as a whole. What’s more, such studies are by and large one-offs that capture the public’s imagination only to subsequently be left by the wayside in favor of whatever new “hot take" on Japanese society comes next.

Maruyama puts forth that the reason for that is because Japan lacks an ideological touchstone—a standard around which to build its own framework and by which to judge and interpret imported ideas. By ideological touchstone, Maruyama is referring to the existence of Christianity in Europe, and the tradition of Confucianism in China. He argues that most of what would be considered Japanese thought was imported from abroad—from Confucianism and Buddhism over a millennium ago to the sudden influx of Western thought following the Meiji Restoration in 1968, as well as democracy in postwar Japan. He also points out that intriguingly, in each case Japan is all too eager to dispense with whatever ideas and values it is entertaining at the time in favor of the newer import.

This tendency to wipe the slate clean when internalizing each new mode of thinking happens because Japan lacks an ideological touchstone. Maruyama argues that this also means that Japan does not built upon ideas of the past, and frequently forgets that ideas that were previously imported; it is constantly rediscovering and re-engaging earlier themes and arguments without ever really building a body of knowledge around them, and thus without ever definitively closing the book on any of them.

This is partly why Japan is so prone to what is called booms (ブーム, that is, cultural crazes that sweep the nation but are promptly forgotten when the next big thing comes along). Several years ago Michael Sandel’s Justice: What’s the Right Thing to Do? sparked a philosophy “boom" in Japan, but people today seem no wiser and no happier, and they retain the lessons in only the most perfunctory of ways.

So does that mean Japan is completely without any original modes of thought? What about Motoori Norinaga’s kokugaku—an academic movement emphasizing Japanese classical studies in the Edo period? (I wrote about kokugaku in BOOKS & MAGAZINES 007.) Maruyama argues that Motoori conceived of kokugaku as an antithesis to the dominant Confucian and Buddhist schools of thought at the time, and was unable to provide a satisfactory logical explanation of the religion of Shinto. He suggests that this fostered an atmosphere that emphasized modes of thought that were sensory rather than rational, which in turn paved the way for ultranationalism and subsequently fascism—leading Japan to war. This is why he saw it as imperative that Japan install democracy as its new (and its first) central ideological touchstone in the postwar era.

At the opposite end of the ideological spectrum was Kobayashi Hideo, whom I covered in an earlier entry in this series. As Kobayashi’s close study of Motoori’s kokugaku would suggest, he believed that Japan did have an ideological touchstone—a tradition of thought. While Maruyama took an objective, logical approach to criticizing Japanese and Western thought, Kobayashi took a more literary, introspective approach to critiquing those same modes of thought.

Maruyama, along with the other “progressive men of letters", harshly criticized Kobayashi for his uncritical, unreserved, and more importantly, patriotic support for Japan during the war. In response, Kobayashi declaimed, “I’m ignorant by nature, and I don’t indulge in reflection. Those of you who are smarter than I should reflect at great length." His words may seem irresponsible at first glance, but his message was actually the opposite: he saw the leftist thinkers’ eagerness to disavow Japan’s past, judge its wartime actions purely based on hindsight, and embrace the new model of democracy as just as dangerous as any ideological trends that had led to the war in the first place.

3.Yoshimoto Takaaki and the Collective Fantasy of the State

The other biggest name among postwar thinkers is Yoshimoto Takaaki, a poet, literary critic, and philosopher from Tokyo. Yoshimoto held contrasting views to Maruyama despite also being on the left. Maruyama sought to import the Western model of democracy to Japan and championed what was called the Shimin-ha (市民派)—those who advocated for citizen participation in society and government. Yoshimoto, on the other hand, dismissed the Shimin-ha and sought a basis for the Japanese nation in the folklore of Japan’s past. This is captured in his 1968 book Kyodo Gensou-ron (a theory of communal fantasy).

In the foreword to the book, Yoshimoto explains that he learned that the state was a communal fantasy by studying Marxism. He was especially surprised to learn that, while the Japanese—and other Asian countries—saw the state as akin to a “bag", which enveloped its citizens completely, Westerners saw the state as a communal fantasy that existed separately from society and rose above it like a superstructure.

Marxism is a socioeconomic theory that originates from the works of 19th century German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Marx observed that in a capitalist society, those who held the wealth only grew richer, and did so while exploiting laborers, whose lives did not improve. He believed that as long as capitalists held a monopoly over society’s capital, that society would never change for the better, and argued that capital had to be confiscated and redistributed. Postwar Japanese leftist thinkers were heavily influenced by Marxist thought.

In Marxism, an economic system and its surrounding social phenomena form a base and superstructure. The base consists of the means of production (tools, machines, factories, and raw materials) and the relations of production (work conditions, division of labor, etc.), which determines society’s other relationships and ideas, which comprises its superstructure (which induces culture, political power structures, rituals, etc.). The influence of the base is predominant, and Marx believed that class struggle was a practical means for effecting social and political changes for the social majority; in other words, he believed that the internal dynamics of a capitalist society would inevitably lead to it being replaced by socialism.

Yoshimoto did not accept the idea that the base held predominant influence over the political relations and social ideologies. Instead, he proposed a viewing the Marxian concept of superstructure as the domain of fantasy. In other words, he asserted that politics, society, culture, thought, and even the economy were all communal fantasies, and suggested that the different aspects of human activities and behavior were governed by fantasy. In the book Kyodo Gensou-ron, Yoshimoto examines Yanagita Kunio’s The Legends of Tono and Japan’s oldest historical text, the Kojiki, in an attempt to understand how the communal fantasy of the Japanese nation came to be.

Yoshimoto’s focus is on ancient Japan, but through his exploration the reader gets as sense of his message for postwar Japanese society. While Maruyama saw the shift from tennosei (the Emperor system) to democracy as a shift from an ideological system to something more rational, Yoshimoto is trying to say that democracy is just another communal fantasy, and is in that regard the same as the tennosei and Emperor worship that came before it. Needless to say, the “progressive men of letters" had a problem accepting his idea of communal fantasy.

4.Fukuda Tsuneari’s Critique of the Democratic Peace Theory Championed by Japan’s “Progressive Men of Letters"

Another critic of the “progressive men of letters" was conservative advocate Fukuda Tsuneari.

Fukuda was born in Tokyo in 1912. He graduated from the English Literature department at Tokyo Imperial University. After graduating, he worked as a middle school teacher and then at a publishing company before starting to work as a literary and cultural critic. After the war, he published numerous critical essays. As a translator, he translated Shakespeare’s four great tragedies—Hamlet, Macbeth, King Lear, and Othello—as well as Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea. He was also active as a playwright and stage producer, adapting Shakespeare as well as staging his own works.

Fukuda became widely known for his 1954 essay “Questioning the Postwar Peace Theory". The support for “progressive men of letters" and their reverence of peace was so predominant that the publisher, fearing a backlash, initially re-titled the essay “Questioning the Implementation of Postwar Peace Theory". In it, Fukuda criticizes the left’s opposition to U.S. military bases, atomic and hydrogen bombs, and the alliance between Japan and the United States. He sees that the left’s view is based on the their belief that people can co-exist in harmony; he questions the evidence that they have that that is actually the case. The essay made waves and established Fukuda as a conservative voice.

One of the distinctive traits of Fukuda’s prose is his use of historical kana orthography—which had been in general use until orthographic reforms after World War II. (Those for the change argued that the historical orthography was no longer in accord with Japanese pronunciation, while those against it argued that historical orthography conveys meanings better.) Fukuda criticized those orthographic reforms and adamantly continued to write and publish all of his works in historical kana orthography. His opinions of the matter are summed up in his book Watashi no Kokugo Kyoshitsu (My Japanese Language Classroom), where he considers the issues facing the Japanese language and critiques the postwar education system.

Reading this book, I was reminded of the ongoing debate regarding Japan’s adoption of the Western name order in Roman script, which is not something Fukuda addresses specifically but is certainly an issue that is tangentially related to his opinions in My Japanese Language Classroom. The Japanese gradually adopted the Western name order in its rush to Westernize following the Meiji Restoration. Now, 150 years later, this tradition is finally starting to change. In May 2019, Foreign Minister Kono Taro—who studied in the U.S.—made a statement to the effect that, as many members of the foreign write the names of Chinese President Xi Jinping and Korean President Moon Jae-in in their native name order, it would be reasonable to ask that the media write Prime Minister Abe’s name not as “Shinzo Abe” but as “Abe Shinzo”. The government has since decided to put surnames first in official Japanese documents as well. It goes to show how closely tied language and names are to national identity.

5.Doi Takeo’s The Anatomy of Dependence and Aoki Tamotsu’s Study of Post-War Nihonjinron

We must also consider Doi Takeo and Aoki Tamotsu for their work in the field of nihon-ron (theories on Japaneseness) and nihonjin-ron (theories on the Japanese people).

Doi Takeo was a Japanese academic, psychoanalyst, and author. He was born in Tokyo, and graduated from the Faculty of Medicine at Tokyo Imperial University, after which he traveled to the U.S. to study at the Menninger Foundation and the San Francisco Psychoanalytic Institute. The culture shock he experienced there would be the catalyst for him to begin his psychoanalytical exploration of contemporary Japanese society. He focused on child rearing and how children are socialized from birth, and came to the conclusion that amae—a culturally ingrained dependence on a mother figure, characterized by the desire to be understood and pampered—is one that pervaded all Japanese relationships and all aspects of Japanese society. Amae is behavior meant to induce another (an authority figure or caregiver) to take care of you, and often takes the form of “acting out" with the tacit knowledge that the other person will indulge you. Doi published his explorations of amae in his 1971 book The Anatomy of Dependence, which was a bestseller in Japan and made amae part of the everyday lexicon. Ezra Vogel, renowned scholar of Japan and China, described it as “the first book by a Japanese trained in psychiatry to have an impact on Western psychiatric thinking."

Why did The Anatomy of Dependence strike such a chord with Japanese readers? In the book Nihon Bunka-ron no Henyou (The Transformation of Theories of Japanese Culture) Cultural anthropologist Aoki Tamotsu points out that Doi’s book was released in a climate where books about Japaneseness and the Japanese identity were becoming increasingly seen as something to be read and enjoyed by the masses. The Japanese economy was at its peak, and with more and more people vacationing abroad and traveling internationally for work, there was a demand for a new conception of what it meant to be Japanese. To put it another way, people were looking for theories that framed Japanese culture in a positive light.

Aoki’s book uses cultural anthropologist Ruth Benedict’s The Chrysanthemum and the Sword (which I covered in BOOKS & MAGAZINES #009) as a jumping-off point to explore 40 years of nihon-ron/nihonjin-ron in postwar Japan. His study identifies four distinct phases:

・The recognition of negative peculiarity, 1945-1954. After Japan lost the war, it shifted its focus to recovery, and a key part of that was the establishment of a democratic political system. As such, intellectuals by and large took a negative view of Japanese society’s traditional structures.

・The recognition of historical relativity, 1955-1963. Japan entered its era of rapid economic growth, and intellectuals recognized how successful Japan had been in modernizing—especially when compared to other Asian countries. They sought to affirm the hodgepodge of Japanese tradition and Western values that had come to characterize Japanese society.

・The recognition of positive peculiarity, 1964-1983. The Japanese economy reached its peak, and books like Ezra Vogel’s Japan as Number One: Lessons for America sung the praises of Japanese society and the Japanese way of doing business.

・From peculiarity to universality, 1984-. Trade friction between Japan and the U.S. resulted in foreign powers taking an increasingly critical look on Japan. People began to realize that while Japanese systems and Japanese styles of business management may work in Japanese society, they present more problems than solutions elsewhere (especially in a multicultural, multilingual, multiethnic environment like the U.S.). The task for Japanese intellectuals became to elevate their discourse from Japanese exceptionalism to something more universal.

Reading these two books leaves you acutely aware that what’s being presented are theories—not works of academic scholarship per se. Many of the concepts are based on anecdotal experiences and feature very little evidence and data-based arguments, and are more a testament to the powers of human observation than they are scientific examinations. This ties back in to Maruyama Masao’s criticism of Motoori Norinaga’s kokugaku.

In my previous article, I wrote about how philosopher Nishida Kitaro argued that there is a Japanese or Eastern worldview that is distinct from the Western worldview, which is based on science and the need to define and quantify things. In that regard, nihon-ron and nihonjin-ron should be recognized on their own terms—albeit taken with a grain of salt.

That being said, at the end of Nihon Bunka-ron no Henyou, Aoki warns, “Affirmations and repudiations of one’s own culture are more often than not characterized by sentimentality (or ideology) rather than rationality, and as such always have a dangerous effect on political discourse." When such discourse becomes too ideological, it has the potential to foster nationalism, spark ethnocentrism, and lead to racial discrimination—and worse.