This is part two of a two-part article on 20th century Japanese film directors. Read part one here.

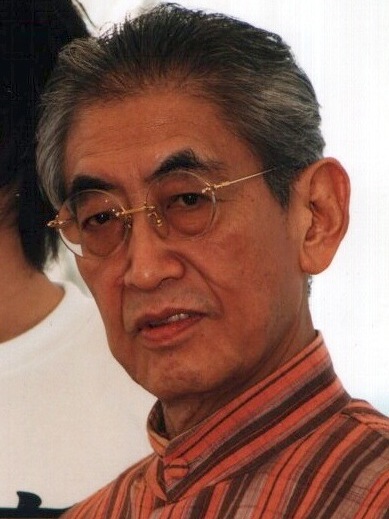

6.Nagisa Oshima

Oshima tackled themes that had long been considered taboo, such as social constraints, the Japanese identity, sexuality, and politics. For that reason he became known as a central figure in the Japanese New Wave movement—a group of young filmmakers that had turned their backs on classical Japanese film. A graduate of Kyoto University and an intellectual, he was an artist with an edgy style, as well as a provocateur who was unafraid to cause controversy. He is infamous for his transgressive explorations of sexuality, but his overarching focus on portraying the challenges facing modern Japanese society would gradually garner him an international reputation as a filmmaker.

Cruel Story of Youth (1960)

The box office success of Cruel Story of Youth, Oshima’s second film, drew widespread attention. The style and anti-authoritarian attitude would draw comparisons with the French New Wave filmmakers, and Oshima and several other Shochiku-affiliated directors came to be called the “Shochiku Nouvelle Vague”. Oshima was named best newcomer in the 11th Blue Ribbon Awards.

In the Realm of the Senses (1976)

In the Realm of the Senses is a French-Japanese art film and fictionalized dramatization of the Abe Sada Incident. The sexually explicit depiction of lust between a man and a woman contains scenes of unsimulated sexual activity, and had to be heavily cut and censored before being allowed to premiere in Japan. The film similarly caused controversy overseas, but gradually earned a reputation as one of the great erotic art films.

Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (1983)

Oshima’s only English-language film, Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence was a worldwide success. The story is centered on the peculiar relationships between four men on a Japanese prisoner of war camp during World War II, and tackles themes such as brutal treatment of prisoners of war and the spirit of Bushido. Renowned musician Sakamoto Ryuichi not only stars, he also wrote the score (his first), which won the film a BAFTA Award for Best Film Music. The title track has since become a Christmas staple in Japan.

7.Yamada Yoji (1931-)

While “Shochiku Nouvelle Vague” directors such as Oshima Nagisa garnered attention and struck out on their own, Yamada Yoji was a more inconspicuous director who remained at Shochiku and continued to make grounded human dramas that depicted people’s daily lives. Much of his work is characterized by a sense of humanity and humor shaped by an interest in rakugo (a Japanese comic storytelling tradition). Now in his nineties, he continues to make work that shines a light on the lives of the common people.

Otoko wa Tsurai yo (It’s tough being a man)

This long running series is centered on actor Atsumi Kiyoshi’s career-making portrayal of Tora-san, a kind-hearted traveling salesman that journeys across Japan to sell his wares. At each destination, he runs into a local “Madonna” (a pretty damsel in distress), and while his clumsy efforts to win her over resolve her circumstances, he is perpetually unlucky in love, and wanders on to further adventures. Of the 48 films made between the 28 years spanning 1969 and 1996, Yamada directed 46 (and wrote or co-wrote the script for all 48). At the peak of the series’ popularity, two films were released a year, one during the New Year holidays, and one during summer.

A Class to Remember (1993)

This film is about the struggles of a group of students—each with his or her own story—who attend a night school in the Shitamachi district of Tokyo. It won several awards at the 17th Japanese Academy Film Prize ceremony, including best picture, best director, and best screenplay. Three sequels were produced, all directed and co-written by Yamada himself.

The Yellow Handkerchief (1977)

This film was inspired by a column series called “Going Home" in the New York Post, specifically one telling a well-known American folk story involving an ex-convict who is trying to return to the home and family he had before he was put in jail. It is a Japanese take on the classic road movie trope, and won several awards at the 1st Japanese Academy Film Prize ceremony, including best film, best director, and best screenplay.

The Twilight Samurai (2002)

Inspired by three short stories by the writer Fujisawa Shuhei, The Twilight Samurai is the tale of a low-ranking samurai in the waning years of the Tokugawa Shogunate. In contrast to the mythical nature of many samurai-centered dramas, Yamada’s approach is historical realism. This was reflected in the visual style, and the darkness of certain scenes set at night or indoors received high praise. At the 26th Japan Academy Film Prize ceremony, the film won every category except best supporting actress; it was also nominated for best foreign film at the 76th Academy Awards.

8.Fukasaku Kinji (1930-2003)

Fukasaku came to prominence in the 1960s with a series of action films starring Shinichi Chiba (aka Sonny Chiba), made a series of genre-defining yakuza films in the 1970s, and later produced hits in such genres as period drama, science fiction, and horror. Although he is known for his graphic depictions of violence, for Fukasaku it is not violence for the sake of violence, but rather a wakeup call to a Japanese populace that has fallen into complacency under its long postwar period of peace. He is highly regarded among foreign filmmakers, and even revered by such iconoclasts as Quentin Tarantino and John Woo.

Battles Without Honor and Humanity (1973)

This yakuza film was adapted from a manuscript written by a real-life yakuza on clashes between different yakuza factions in postwar, bombed-out Hiroshima. Unlike most yakuza films, which sought to romanticize their subjects in an almost heroic light, Fukasaku uses a documentary-like style to depict gritty violence and the feud between factions as realistically as possible. This film was ranked fifth in a list of the 200 best Japanese films of all time, published by Kinema Junpo in 2009.

Fall Guy (1982)

Based on a play by major playwright Tsuka Kohei, Fall Guy is a romantic comedy/drama centered on the Kyoto film studios of Japanese film company Toei. It is the story of the peculiar relationship between a period drama star, a bit player, and the actress the former has accidentally impregnated. It was ranked number one in that year’s Kinema Junpo top ten list, and won many awards at the Japan Academy Film Prize ceremony, including best film, best director, and more.

House on Fire (1986)

The term “house on fire” is a Buddhist metaphor that compares the worldly passions and desires that define our existence to being inside of a house that is on fire and about to be burned to the ground. This film is based on the autobiographical novel by Japanese novelist Dan Kazuo, and tells the story of a freewheeling protagonist and the women he becomes involved with. It won the best film prize at the 10th Japan Academy Film Prize ceremony.

Crest of Betrayal (1994)

Fukasaku had already adapted the story of the forty-seven ronin in his 1978 film The Fall of Ako Castle, but Crest of Betrayal is a horror story that combines the classic samurai legend with Yotsuya Kaidan—a tale of ghostly revenge that is set in the same era. The film won best film, best director, and best screenplay at the 18th Japan Academy Film Prize ceremony, and is one of Fukasaku’s best known later works.

9.Itami Juzo(1933-1997)

After working as a commercial designer and actor, Itami made his directorial debut at 51 with The Funeral, which was a massive success in Japan. The following year he would become an internationally regarded filmmaker with the “ramen western” film Tampopo. (Tampopo retains a 100% fresh score on the film review site Rotten Tomatoes.) In 1997, he was found dead in front of the building where his office was located. What appeared to be a suicide note was found left in his office, leading police to conclude that Itami had jumped to his death; however, from the day of the incident there has been much conjecture about what actually transpired. Itami had already been attacked once in 1992, after releasing a film about yakuza racketeering (Minbo), and at the time of his death he was said to have been working on another film dealing with yakuza. One theory is that his murder was staged as a suicide by members of said factions. Itami’s father was satirical filmmaker Itami Mansaku, his wife was actress Miyamoto Nobuko, and his brother-in-law was Nobel Prize-winning writer Oe Kenzaburo.

The Funeral (1984)

Itami’s directorial debut deals with the austere tradition of funerals with his characteristic comedic sensibilities. It was a massive success in Japan, and won several awards at the 8th Japan Academy Film Prize ceremony, including best film, best director, and best screenplay. Kinema Junpo ranked it number one in its list of top ten films from 1984.

A Taxing Woman (1987)

A tax auditor for the Japanese National Tax Agency investigates tax evaders and uncovers their crimes, but meets her match in the owner of a chain of love hotels. After the success of The Funeral, the income Itami earned put him into a higher tax bracket, and he was reportedly inspired to make this film after a massive chunk of his earnings was collected as a reward for his newfound financial success. The film won six awards at the 11th Japan Academy Film Prize ceremony, including best picture, best actress, and best actor.

10.Epilogue: Japan as a nation that refuses to grow up

When mobile phones first became widespread in Japan, marketers took note of what they called Galápagos syndrome, which Wikipedia defines as “an isolated development branch of a globally available product."

The Japanese population may be dwindling due to low birthrate, but as of 2018, it is still home to 127 million. In comparison, the U.K. has a population of 65 million, France 67 million, and Germany 80 million. Among developed nations, Japan has a relatively large population for its size. (Side note, the population of the U.S. is around 320 million, and Russia 140 million.)

That relatively large population puts Japan in an in-between state, not completely insular, but not truly international, either. For many Japanese companies that means that they have a reliable domestic market for otaku-oriented products (otaku in the general sense of obsessiveness to an unhealthy degree).

Although the fastest growing demographic of Japanese society is the elderly, consumption continues to be centered on the younger demographic, and as a result the majority of products that are developed are essentially intended for children.

That trend is best exemplified in the vast market of video games, anime, and Japanese idol culture.

These franchises benefit from having not just one central product but a whole array of related products, services, and media—which are often sold for a premium. Product development has largely shifted in this direction, and fewer and fewer products are being marketed specifically for older, more discerning audiences.

And the Japanese government (specifically the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry) has capitalized on these trends, weaponizing childlike innocence and otaku culture and marketing it overseas under the name of “Cool Japan".

Japanophiles who were drawn to Japan through its traditional culture may have looked upon this strategy and rolled their eyes; I sure did. What would compel government bigwigs to put otaku culture at the center of its message when Japan has no shortage of literature, films, technology, food, and architecture worth promoting to the world (the above films being a prime example)?

Well, it seems that the government has finally caught on—otaku culture is no longer the main pillar of the “Cool Japan" promotional effort. But in the meantime it did serve to shine a light on just how many of the politicians and bureaucrats here possess perverted tendencies.

And Japanese TV continues to be endlessly fascinated with showing how obsessed overseas otaku are with Japanese culture. What they neglect to show is that in Western societies, otaku are a subculture, and do not represent society as a whole. There is something cringe-inducing about someone who choses to wear the weeaboo label proudly.

There is more to celebrate about Japanese culture than wearing character-themed merchandise and dyeing your hair blue or green.

It has become clear that in the years to come, Japan will have to bring in foreign workers in various fields to compensate for its dwindling population.

In order to welcome these foreigners and draw a wider range of visitors beyond that, it is imperative that Japan “grows up" as a country. The sooner the better.

Instead what you see is the Diet fumbling about, getting in the way of progress by fixating on every small mistake it can dig up on the actions of those in power. It’s no surprise that the world sees Japanese politics as a place where childishness and pettiness reigns. Left-wing members of the Diet should recognize that their words and actions damage Japan’s international reputation.

To them I would say, accept the fact that people make mistakes, and take heed from the idea of penance in the Catholic church. There is no virtue to calling for blood.